Control Characters

31 May 2020 | categories: blog

prev: Default Text Width | next: Ruby: Blocks, Procs, and Lambdas

If you’ve used a computer before you’ve no doubt used a control character, these

are the characters you need to hold down the control key before pressing. One of

the most well known would be ctrl-c to stop a script or program, and another

is ctrl-z which suspends a running process (useful if you use Vim and need to use

the shell for a moment).

Control characters are interesting things and one I feel deserve a blog post because there is some history there and the way they work is fascinating to me. Let’s jump in.

a brief history

As is usually the case with computers the history of these control characters predate computers, people have needed a way to transmit something other than their message for quite a long time.

morse code

This is a bit of a stretch but you can see a form of control characters in Morse code as Prosigns (procedure signs). Here are a few prosigns:

·—·—unknown station·—···wait········correction

They are basically a way for one operator to convey an action or other information to the other operator, a way to say “hey this isn’t part of the message but I need to tell you X”.

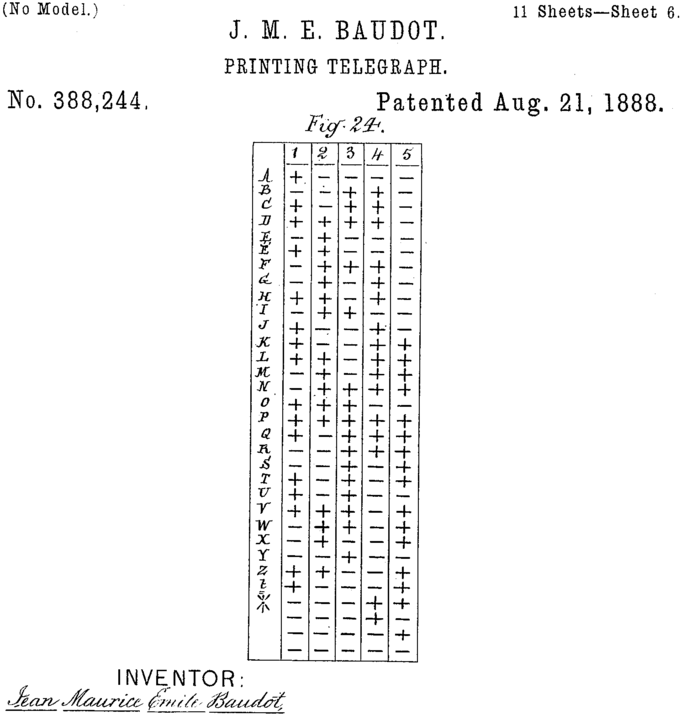

baudot code

Baudot code is an early character

encoding system invented in 1870 by a man called Émile

Baudot. In this code 5 bits

are used to encode every single letter of the Latin alphabet as well as some

control signals like DEL and NUL. The devices this encoding was used on

resembled small pianos as opposed to typewriters that came along a little later.

The rate at which you could send characters over the wire was known as the baud rate, and is still something you can run into when dealing with different terminals.

By Jean Maurice Emile Baudot - Image Full patent, Public Domain, Link

murray code

The Baudot code was cool and all but a chap called Donald Murray came along and invented the telegraphic typewriter AKA teletypewriter or teletype. Not only did he envision using a typewriter to send telegraphs but he figured the Baudot code needed beefed up, so in 1901 he came out with something which would end up being called Murray code.

It was this change that introduced what became known as “control characters”.

Fan favourites such as CR (carriage return) and LF (line feed) were added. Ever

wondered why the enter button on your keyboard is sometimes called return? It’s

because it translates to a ‘carriage return’, and if you were using a

teletypewriter it would cause the carriage holding the paper to “return” back

to its original position, and the ‘line feed’ would move the paper up enough so a new

sentence could start.

Murray also added a BEL (bell) code which would ring a physical bell to alert

the operator, nowadays the BEL character just causes your terminal to make a ding

sound. It’s at this point it’s clear to see that these control characters are

for controlling devices, hence the name.

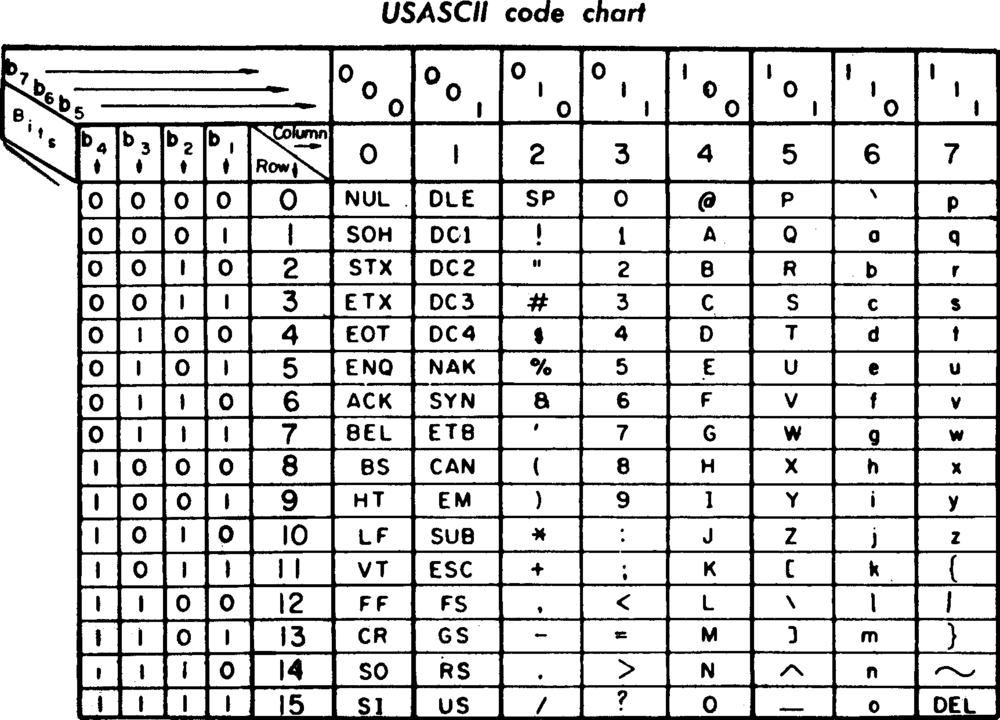

ASCII

Let’s jump ahead in time a little bit to 1963 for the debut of the 7-bit

encoding called ASCII. ASCII stands for

American Standard Code for Information Exchange, and this encoding leads us

nicely into the present day control characters. The encoding is based on the

English alphabet and encodes 128 characters, there are only 26 letters in the

alphabet so that leaves us plenty of room for things like punctuation, and

saucy characters like <, ~, and %.

By an unknown officer or employee of the United States Government - http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/GE/GE.TermiNet300.1971.102646207.pdf (document not in link given), Public Domain, Link

There was also room for plenty of new control characters and ASCII originally

specified 33 non-printing control characters, these characters included the

previously mentioned CR, LF, BEL, and DEL characters, but also added new

ones like BS (backspace) and HT (horizontal tab).

The control characters in ASCII take up the first 31 spaces in the encoding,

apart from DEL which still sits at 127 or 7F in hexadecimal, which is where it

was originally found in Baudot code.

flipping bits

I know this post is about control characters but I would be remiss if I didn’t

take a little time to point out how clever the ASCII system was. In this system

the capital letters come before lower case, letter A is 65 or 41 in hex, and

lowercase a is 97 or 61 in hex.

The reason I’m including the hexadecimal with the decimal is it’s slightly

easier to see what I’m going to point out, a’s number is 32 higher than A

and 32 in hexadecimal is 20. The reason this is important is you can get from one

letter to it’s lower/upper version by flipping the 6th bit.

1000001 - A

1100001 - a

1000010 - B

1100010 - b

ASCII chart

There is a man page for ASCII, if you have a look you should find a chart in there which looks something like the chart below. The chart shows the octal, the decimal, and the hexadecimal that represents the character which sits in the “Char” column. Two characters and their different base representations fit onto a single line.

Oct Dec Hex Char Oct Dec Hex Char

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

000 0 00 NUL '\0' (null character) 100 64 40 @

001 1 01 SOH (start of heading) 101 65 41 A

002 2 02 STX (start of text) 102 66 42 B

003 3 03 ETX (end of text) 103 67 43 C

004 4 04 EOT (end of transmission) 104 68 44 D

005 5 05 ENQ (enquiry) 105 69 45 E

006 6 06 ACK (acknowledge) 106 70 46 F

007 7 07 BEL '\a' (bell) 107 71 47 G

010 8 08 BS '\b' (backspace) 110 72 48 H

011 9 09 HT '\t' (horizontal tab) 111 73 49 I

012 10 0A LF '\n' (new line) 112 74 4A J

013 11 0B VT '\v' (vertical tab) 113 75 4B K

014 12 0C FF '\f' (form feed) 114 76 4C L

015 13 0D CR '\r' (carriage ret) 115 77 4D M

016 14 0E SO (shift out) 116 78 4E N

017 15 0F SI (shift in) 117 79 4F O

020 16 10 DLE (data link escape) 120 80 50 P

021 17 11 DC1 (device control 1) 121 81 51 Q

022 18 12 DC2 (device control 2) 122 82 52 R

023 19 13 DC3 (device control 3) 123 83 53 S

024 20 14 DC4 (device control 4) 124 84 54 T

025 21 15 NAK (negative ack.) 125 85 55 U

026 22 16 SYN (synchronous idle) 126 86 56 V

027 23 17 ETB (end of trans. blk) 127 87 57 W

030 24 18 CAN (cancel) 130 88 58 X

031 25 19 EM (end of medium) 131 89 59 Y

032 26 1A SUB (substitute) 132 90 5A Z

033 27 1B ESC (escape) 133 91 5B [

034 28 1C FS (file separator) 134 92 5C \ '\\'

035 29 1D GS (group separator) 135 93 5D ]

control characters

With all of that history out of the way I can now get into the meat of what spurred me into writing this post, much like the one bit difference between upper and lower case letters in ASCII there is a pattern which links control character sequences that we type and the control characters that they represent.

I’ll give some examples of commonly used control characters and using the table above see if you can spot the pattern.

ctrl-his the same as hitting the backspace keyctrl-[is the same as hitting the escape keyctrl-mis the same as hitting the return keyctrl-jis the same as hitting the enter keyctrl-iis the same as hitting the tab keyctrl-dcan be used to signal end of input

These examples can be used on the command line or in vim, I’m sure you can use them in other places but those two places are where I spend most of my time on a computer.

Side note: it occurred to me while researching this that the control key is named such because it is what you need to hold down to enter a control character. This is like the time I realised breakfast is called so because you’re breaking the fast, or fireplace is where the fire should be placed. Crazy.

patterns

Let’s take the first example ctrl-h and check out the chart

Oct Dec Hex Char Oct Dec Hex Char

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

010 8 08 BS '\b' (backspace) 110 72 48 H

Cutting the chart down like this shows that there is a relationship between the

characters that are listed on the same line, somehow an H is related to BS.

Looking at the hexadecimal for H (48) and the hexadecimal for BS (08) you

can see the difference is 40, or 64 in decimal.

64 is a power of 2, so just like our upper case and lower case example before,

you can get from the character H to BS by flipping a single bit, in this

case the 7th bit instead of the 6th.

1001000 - H

0001000 - BS

I won’t go through the hassle of writing the binary out for the other control

characters but hopefully you can see just flipping the 7th bit gets us from H

to BS. In essence when you hold down a control key and hit a key, you are

flipping the 7th bit, allowing you to type a control character.

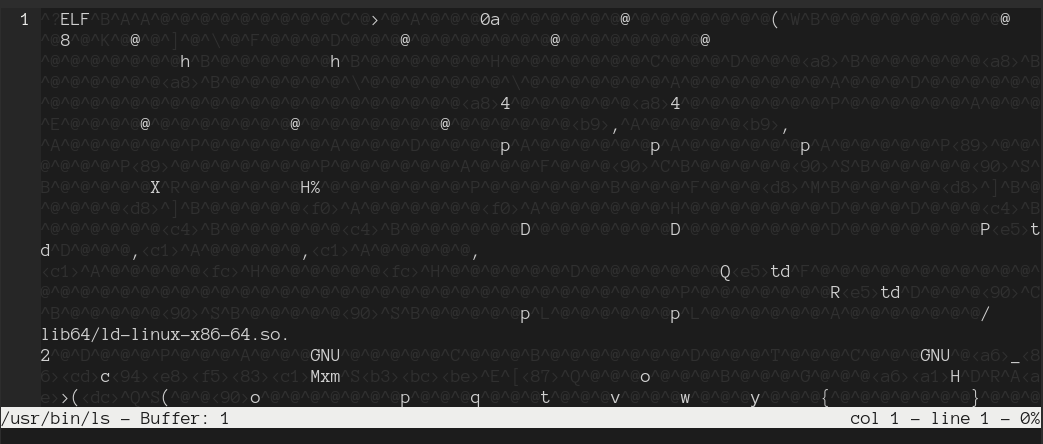

This also explains why, if you open a binary file using vim you will see ^@

all over the place. In ASCII 00 represents NUL, and its control

character is ctrl-@, and the caret symbol is another way to represent ctrl.

in conclusion

Computers have a fascinating history! I think that goes without saying, and I just love that I can find something that piques my interest and it will take me back to the 1800s as I look for answers. This one involved telecommunications before it was hip, old character encoding systems, and bit flipping.

ASCII isn’t the end of the road when it comes to character encodings by the way, there are just too many languages and characters in the world that ASCII was not fit for purpose. The internet grew and the world became more and more connected, ASCII clearly was unable to be the encoding that would facilitate global communication, the world moved on and UTF-8 was invented to deal with the short comings of ASCII. UTF-8 is a blog post for another day.

Who knew control characters and character encoding systems could be so interesting?