git: ours and theirs

24 Oct 2020 | categories: blog

prev: git reset | next: git revisions

Every now and then you run into problems when merging or rebasing branches using git, and to make things worse your editor might ask you to accept “our” changes or “their” changes. Not prepared to give git the satisfaction of playing its little game you choose one and hope for the best which inevitably turns out to be the wrong one and you need to restart the merging/rebase process anew.

Okay maybe I’m projecting my experiences onto you, dear reader, but if you experience confusion when faced with merge conflicts and needing to make a decision on which changes to keep then this post is for you.

I seem to say this in all of my git posts but having a clear mental model of what git is doing during certain operations really helps, my goal here is to help you understand what git is doing and what it needs from you when you encounter conflicts.

what is a conflict

Alright, this might be a little basic but let’s discuss what a conflict actually is, understanding what a conflict is will help us in later sections.

When you perform an operation that needs to merge two commits or branches together and the two changes are trying to affect the same place in a file then git can’t make the decision of which change to keep so it pesters you instead.

I’ve set up a very simple git repo with two branches master and dev:

A--B <- master

\

C--D <- dev

As you can see dev branches from master at commit A, commit A is

considered the common ancestor of dev and master. In the mean time

master has created a new commit B and dev created two new commits C and

D.

All good, except the changes in commits B and D alter the same line in the

same file. Here is the change master has made:

> git --no-pager show -1

commit 47e7876df1a535e94fd86faea6f59bfb979b1358 (HEAD -> master)

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sat Oct 24 07:45:07 2020 +0100

B

diff --git a/my_file b/my_file

index 97a576e..677fa23 100644

--- a/my_file

+++ b/my_file

@@ -1 +1 @@

-change A

+change B

And here are the changes dev has made, commit C adds a new file whereas D

alters my_file:

> git --no-pager show -2

commit aae7bc9137098b8338170a81855c12624f7ae3ec (HEAD -> dev)

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sun Oct 25 07:27:48 2020 +0000

D

diff --git a/my_file b/my_file

index 97a576e..10401a3 100644

--- a/my_file

+++ b/my_file

@@ -1 +1 @@

-change A

+change D

commit 4e6889592e3718229ed227f5d1da58ad802daba6

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sun Oct 25 07:27:24 2020 +0000

C

diff --git a/second_file b/second_file

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..e0c8b34

--- /dev/null

+++ b/second_file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+separate change

Due to the fact these two commits B and D have made conflicting changes to

the same file if we were to try to merge or rebase dev and master now we

will get conflicts because git has no idea which of these two changes to apply,

thus you get brought in to make the decision.

merging

Let’s pull the trigger and try merge dev into master just so we can see what

happens.

> git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

> git merge dev

Auto-merging my_file

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in my_file

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Oh no, we have a conflict in my_file. If we check git status and use the

--short option it shows us that my_file has the state U for the changes on both

sides of this merge, and second_file has the status A.

The left U is for the index and the right U is for the working tree, U

stands for “updated and unmerged”. A means “added”, there were no issues with

second_file so it was successfully added in the index.

> git status -s

UU my_file

A second_file

And inside my_file we have some conflict markers lovingly inserted for us by

git.

> cat my_file

<<<<<<< HEAD

change B

=======

change D

>>>>>>> dev

The first section marked <<<<<<< HEAD down to ======= are the changes that

master would like to make. We are currently on the master branch so HEAD

points to commit B.

> cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/master

> cat .git/refs/heads/master

47e7876df1a535e94fd86faea6f59bfb979b1358 # <- commit B

And the section ======= to >>>>>>> dev shows the changes from dev, in

other words the branch we are merging in to master.

In some text editors and IDEs they have functionality which allows you to sort

out your conflicts and usually they present them as our and their changes,

and without the proper context it’s easy to see why this can get confusing.

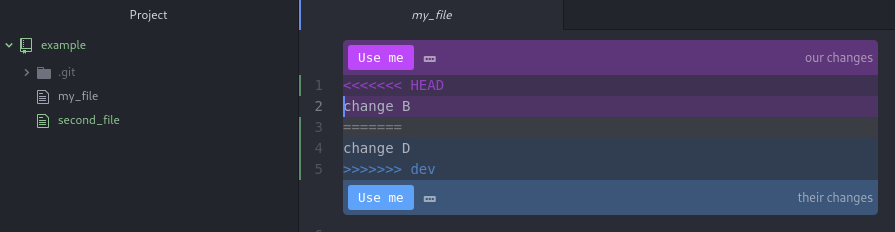

Atom will show the changes like this:

ours or theirs?

In order to try and merge these branches we first checked out master so in

essence we are master. The changes in commit B are our changes.

We are trying to merge in changes from a different branch dev, seeing as it’s

a different branch than the one we are on we should consider any changes

they make to be their changes.

As I said it’s easy to see why this is confusing, personally if I’ve been

working on dev all day then I would consider the changes in dev to be my

changes, i.e. ours, but the reality is things are the opposite to what you

would be expecting.

Git doesn’t think like that, it has no idea what you’ve been up to all day, it

has just been asked to merge two branches. During a merge conflict brought about

by trying to merge branches it will consider anything HEAD is

pointing to to be ours (HEAD is pointing to the same commit that master

is pointing to) and the commits it’s merging into HEAD will be theirs.

In short:

When resolving conflicts from a bad merge “our changes” are from the branch you are merging into, and “their changes” are from the branch being merged in, typically “their changes” are from your feature branch.

To make things fun this way of thinking about conflicts doesn’t always apply, for example rebasing is the complete opposite…

rebasing

Now instead of merging the dev branch into master we want to rebase dev,

instead of this history:

A--B <- master

\

C--D <- dev

We would like this history:

A--B <- master

\

C--D <- dev

We want to change the common ancestor between the two branches from A to the

new B commit on master.

Unlike our merge from before we don’t need to be on master to accomplish this

because we are making changes to our dev branch, so we need to checkout dev.

> git checkout dev

Switched to branch 'dev'

> git rebase master

Created autostash: 15e3f17

HEAD is now at 124c8df D

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: C

Applying: D

Using index info to reconstruct a base tree...

M my_file

Falling back to patching base and 3-way merge...

Auto-merging my_file

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in my_file

error: Failed to merge in the changes.

Patch failed at 0002 D

hint: Use 'git am --show-current-patch' to see the failed patch

Resolve all conflicts manually, mark them as resolved with

"git add/rm <conflicted_files>", then run "git rebase --continue".

You can instead skip this commit: run "git rebase --skip".

To abort and get back to the state before "git rebase", run "git rebase --abort".

That’s a lot of spiel just to tell us that there is a conflict when trying to

apply commit D, let’s see what git status tells us about the file.

> git status -s

UU my_file

Righto, conflicts. second_file doesn’t appear this time, but that’s to be

expected and will make sense when I dive deeper into the rebasing process down

below. Now what is in my_file?

<<<<<<< HEAD

change B

=======

change D

>>>>>>> D

Interesting, it’s similar to but not the same as the conflict markers when

merging. HEAD always points to the current commit you are on and by the looks

of it it’s pointing to commit B and the bottom section is showing the change from

commit D instead of the branch dev, like it did when we were merging..

When we were merging before I showed you that HEAD was pointing to master, but

if we check HEAD now we will see it’s pointing to an actual commit object

instead.

> cat .git/HEAD

f566f18c2fc995e3b5cb67857eeb4e5e4cb644ce

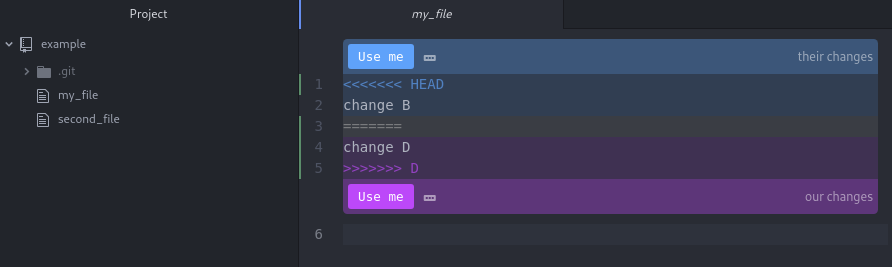

On top of that what is considered “ours” and “theirs” has switched, an IDE will show the changes like this now:

I seem to have created more questions than I have answered in this section, what

would really help here is an understanding of what git rebase does, so let’s

take a step back and look step by step at what git did there.

what is rebase doing?

When we started we were on our dev branch and things looked like this:

A--B <- master

\

C--D <- dev (HEAD)

dev is pointing to a commit and HEAD is pointing to dev.

> git rev-parse --short master

47e7876

> git rev-parse --short dev

aae7bc9

> cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/dev

And because it will aid in discussion very shortly here are the commit hashes on

the dev branch:

> git --no-pager log --oneline

aae7bc9 (HEAD -> dev) D

4e68895 C

71764fc A

And here is what master can see:

> git checkout master && git --no-pager log --oneline

47e7876 (HEAD -> master) B

71764fc A

When we had the dev branch checked out we ran git rebase master and the

first thing git did was take the changes in commits C and D and put them in

the temporary area then it pointed HEAD to the commit master is pointing at:

B (47e7876). dev was left still pointing to commit D (aae7bc9).

> git rebase master

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: C

Applying: D

Using index info to reconstruct a base tree...

M my_file

Falling back to patching base and 3-way merge...

Auto-merging my_file

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in my_file

... # output elided for brevity

Git then goes through the changes in the temporary area and applies them one by

one to the commit that HEAD is pointing to, if a change is successfully

applied git will create a new commit and HEAD will be updated to point at this new

commit. This explains why in our conflict markers during a rebase we get the

commit message instead of the branch name, each change is applied separately and

not all at once like in a merge.

<<<<<<< HEAD

change B

=======

change D

>>>>>>> D # <- message of commit being applied

In the rebase output above git successfully created commit C so at that

exact moment the git history looked like this, note that the changes from D are

still sitting in the temporary area:

C' <- HEAD

/

A--B <- master

\

C--D <- dev

# temporary area

D

This new commit C' has the same changes and the same commit message as C but

it’s a new commit with a new hash 9d41e4a, it’s completely different to the one

that is in dev’s history that has the hash 4e68895.

> git --no-pager log --oneline

9d41e4a (HEAD) C

47e7876 (master) B

71764fc A

Git then tried to apply D to HEAD but it ran into a conflict and added

conflict markers to my_file and paused the rebase operation waiting for us to

make a decision.

This brings us back to where we were before our time travelling adventure. Our file now looks like this:

<<<<<<< HEAD

change B

=======

change D

>>>>>>> D

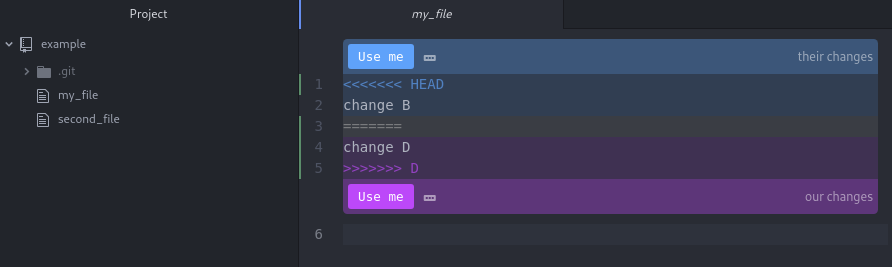

And an editor is showing us this:

Based on what we know about merge conflicts you can see why it’s easy to get

incredibly confused about what’s happening right now. Previously during a

conflicted git merge operation HEAD represented our changes but now it

represents their changes.

This operation requires us to think slightly differently than before when we were merging.

The way I like to think about this one is we never really left dev, we are

rebasing dev so all of the changes in the temporary area are our changes.

As the rebase works through the changes in the temporary area it builds up a new

branch that HEAD tracks, the key thing here is we are applying our changes

to this new branch.

> git mergetool

Merging:

my_file

Normal merge conflict for 'my_file':

{local}: modified file

{remote}: modified file

4 files to edit

> git rebase --continue

Applying: D

When we resolve the conflicts and run git rebase --continue then git will update

the dev reference file to point to the head of the new branch that HEAD was

tracking, and HEAD is updated to point to dev.

> cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/dev

> cat .git/refs/heads/dev

6a7ba28d00e64ee59a6067d0cff74ab8dd99be70

Our history now looks like this:

C'--D' <- dev (HEAD)

/

A--B <- master

In short:

When resolving conflicts during rebasing “our changes” are the changes being taken from the temporary area, i.e. our feature branch, and “their changes” are from the new branch that is being built.

Another way to think of this is when you’re rebasing your feature branch then “our changes” really are our changes.

It requires a little thought but I hope I’ve explained it well enough where it doesn’t take mind numbing mental gymnastics to work things out.

how does git know?

So during a conflict how does git know what changes belong to whom? I alluded to this in my last post on Git reset, this information is stored in the index file.

To explain this let’s we jump back to the middle of the rebase conflict when git

was needing help with applying commit D.

C' <- HEAD

/

A--B <- master

\

C--D <- dev

And my_file contains the conflict:

> git status -s

UU my_file

> cat my_file

<<<<<<< HEAD

change B

=======

change D

>>>>>>> D

We can use ls-files to peer inside our index file and see what git sees.

> git ls-files -s

100644 97a576edf83a718abb9b13c1822e4476c6899b68 1 my_file

100644 677fa23a90ce8aa8a57c2fa2e581927da853af07 2 my_file

100644 10401a36c0bae1a144eca44f3a124b8a61faaf7c 3 my_file

100644 e0c8b340a1b7f76dd7b02bb62480cbfd45d4e9a2 0 second_file

I broke down what this output means in my Git reset post but today we are just going to focus on the numbers in the third position, these represent the stage of the change.

There are currently three entries for my_file in the index, each with a

different number, and second_file has a different number than all the others.

These numbers mean:

0- “normal”, un-conflicted, all-is-well.1- “base”, the common ancestor version.2- current branch (HEAD) version.3- the branch being-merged-in version.

See the “3-Way Merge” section in man git-read-tree for more detailed

information on these stages. Any time you try to merge some branches together

you git will add this information to the index file.

Let’s have a look at each of the blobs for my_file and see what

they contain. Starting with 1 — the base version.

> git cat-file -p 97a576

change A

And 2 — the version HEAD sees:

> git cat-file -p 677fa

change B

And 3 - the version being merged in:

> git cat-file -p 10401a

change D

You may have noticed here that there is no “ours” or “theirs” anywhere in here,

that’s because it’s up to the porcelain commands git merge or git rebase, or

user created scripts/programs to interpret the stage numbers. The .git folder

contains other clues as to what operation resulted in these conflicts which is

how editors like Atom can figure out what changes are “ours” and “theirs”.

As we’ve already discussed in this post 2 and 3 would be ours and theirs

respectively when you are merging branches, whereas 2 and 3 would be

theirs and ours when you’re rebasing.

conclusion

Shit is confusing! Well, I hope a little less so now I’ve explained the logic behind what’s happening. I would recommend reading the man pages for the various git commands, they are full of information so go forth and educate yourself!

man git-rebaseman git-mergeman git-read-treeman git-ls-filesman git-status