git reset

10 Oct 2020 | categories: blog

prev: git revert | next: git: ours and theirs

I am back again to talk about git, this time I wanted to focus on git reset

and what the various options --soft, --mixed, and --hard are and the

different ways you can use the command. I want to talk about git reset because

to understand the various ways you can use the command you really need to

understand the life cycle of files when working with git. That means I would

also need to explain the various stages you can think of a file as being in and

I love explaining shit.

Any time I have a chance to build a slightly better mental model of git I’m going to take it because understanding something as fundamental as the flow of a file from untracked to committed really fucking helps in the long run.

high level

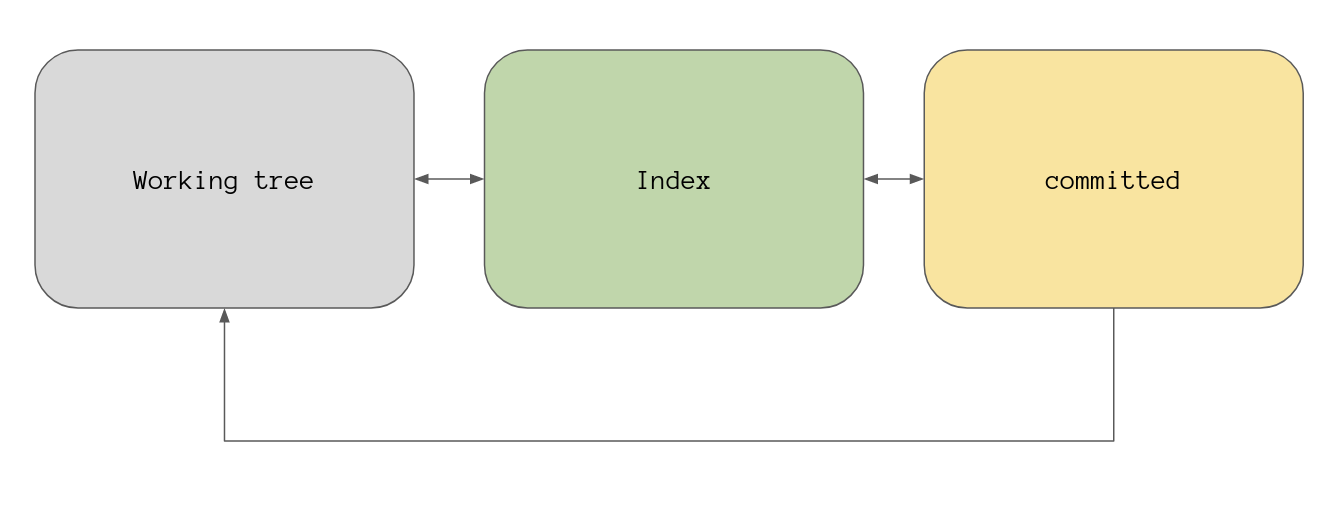

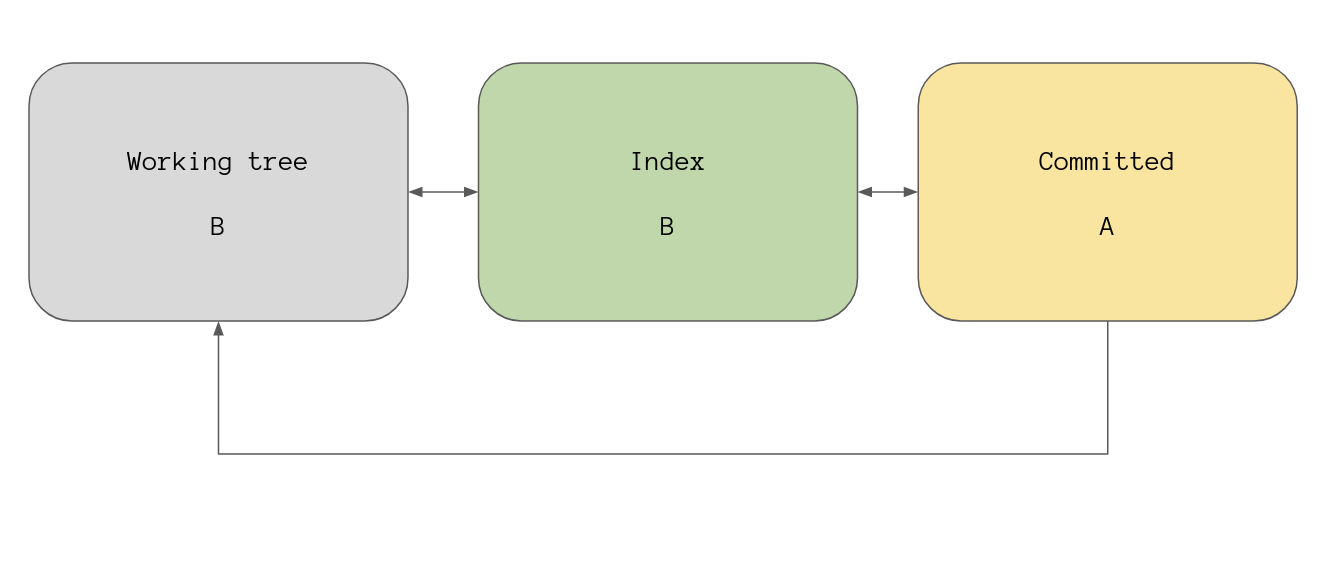

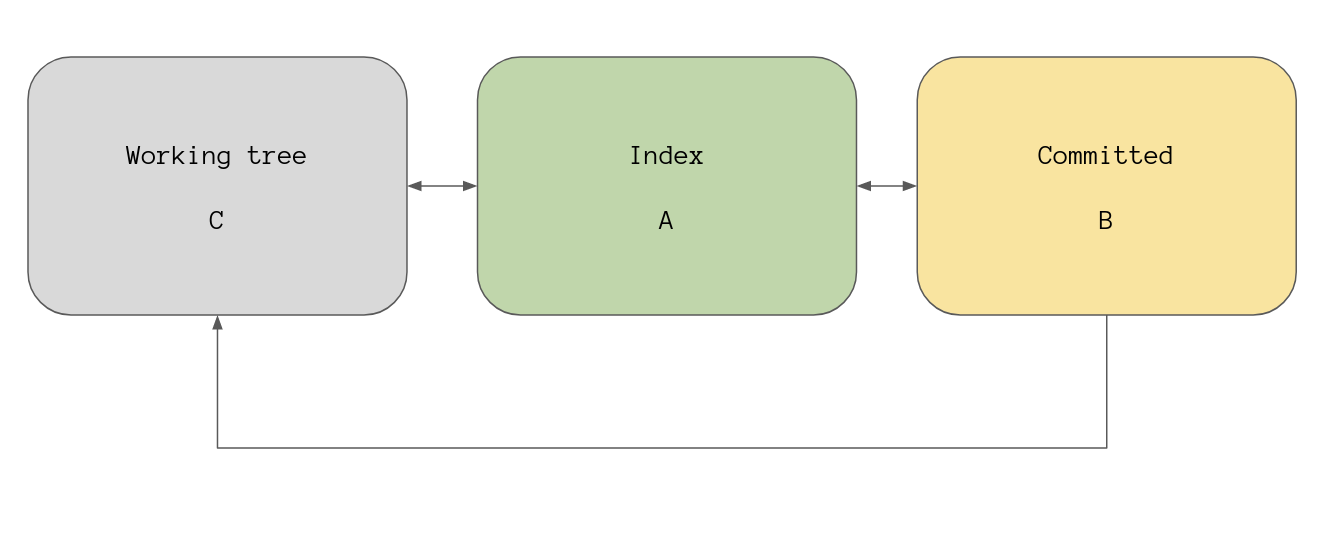

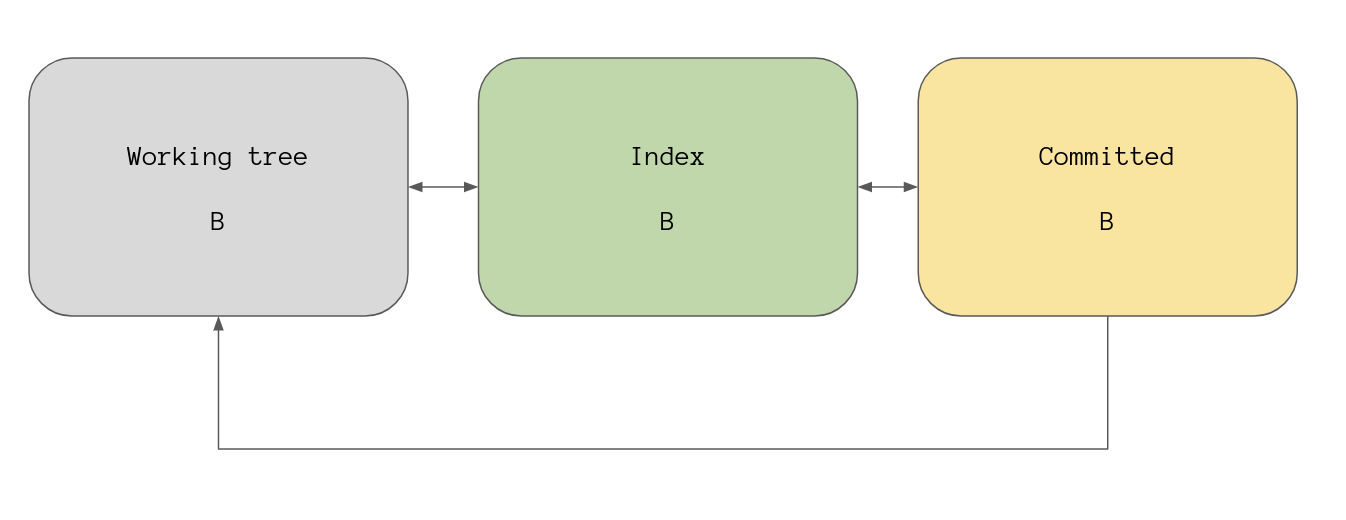

To start I spent weeks designing and drawing the following diagram (you’re

welcome) to show there are three places you can think of a file as being: in the

working tree, in the index, or committed. The arrows show the various ways you

can move a file between these stages using git commands. Spoiler: you can use

git reset for some of these movements.

I’ll go over each of these stages but if you want a much deeper insight into what git is doing have a read of a post I wrote a while ago called How Git Works, that post gets very low level if that’s your sort of thing.

For this post however I’ll keep it as high level as I can, let’s start from the working tree.

the working tree

The working tree as it’s known in git is really just your working directory,

it’s all the files you can currently see in your directory. More specifically

it’s everything in the directory that isn’t the .git directory.

> git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /tmp/skip/.git/

> echo state A > file

> ls -Al

total 8

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 3 Oct 11 11:14 file # <- in working tree

drwxr-x--- 5 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:13 .git # <- not in working tree

git status shows you the relationships between the working tree, the index,

and committed stages. In other words how do the references to files in these

areas differ? Running it now will show us the path for any files in the

working tree that aren’t tracked by git, we should expect file to show up

here.

> git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

file

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

What git status is showing us here is what we could commit if we added this

file with git add.

This is really simple so I won’t dwell on it, working tree equals files that

don’t live in .git that you can edit/delete/modify. Let’s check out the next

stage, the index.

index

If we look inside the .git folder we should see a bunch of stuff that is

needed by git. An important one here is the HEAD file which just contains the

hash of the commit that our branch is currently pointing to. Right now it’s

empty. We’ll be changing HEAD pretty extensively later using git reset.

> ls -Al .git

total 20

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 92 Oct 11 11:13 config

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 23 Oct 11 11:13 HEAD # <- tip of current branch

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:13 hooks

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:13 objects

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:13 refs

Let’s use git add to stage file and have another look inside .git.

> git add file

> ls -Al .git

total 24

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 92 Oct 11 11:13 config

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 23 Oct 11 11:13 HEAD

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:13 hooks

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 104 Oct 11 11:16 index # <- welcome to the party!

drwxr-x--- 5 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:16 objects

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Oct 11 11:13 refs

There is a new file called index and this is the file that holds information

on tracked content, it is a view of what would be committed if you were to use

git commit right this second. This file is also known as the cache, the

staging area, or staging.

The index is a binary file so we can’t just open it up and look at it as you

might probably want to do, you could use xxd to view a hex dump if you want…

> xxd .git/index

00000000: 4449 5243 0000 0002 0000 0001 5f82 dc32 DIRC........_..2

00000010: 2fdc 47da 5f82 dc32 2fdc 47da 0000 fe01 /.G._..2/.G.....

00000020: 0013 fca4 0000 81a4 0000 03e8 0000 03e8 ................

00000030: 0000 0008 5165 4802 d7a7 590f 1744 b7a6 ....QeH...Y..D..

00000040: f666 1f5f cf67 8799 0004 6669 6c65 0000 .f._.g....file..

00000050: 0000 0000 db99 d874 0aa4 0a8f 61e5 bb2e .......t....a...

00000060: 1e8c 569c e3c3 8970 ..V....p

… but I’m just going to use the git plumbing command

ls-files to peak inside the index file

and get human readable output, we can see staged content by passing the --stage option.

> git ls-files --stage -v

H 100644 51654802d7a7590f1744b7a6f6661f5fcf678799 0 file

When we ran git add in the previous section git took the content of file

and created a blob for it, saved it in .git/objects/ then updated the index

with a reference to it.

Breaking apart the line we got back from ls-files we have an H at the start

of the line which means “cached”, the different values you can have here are:

H- cachedS- skip-worktreeM- unmergedR- removed/deletedC- modified/changedK- to be killed?- other

Next we have 100644 which are the file permissions.

Then 516548... which is the SHA-1 hash value of the file contents.

After that is 0 which is the stage number, this value is only really needed

when handling merge conflicts, the different values you can have are:

0- “normal”, un-conflicted, all-is-well.1- “base”, the common ancestor version.2- “ours”, the target (HEAD) version.3- “theirs”, the being-merged-in version.

And finally there is the name of the file: file.

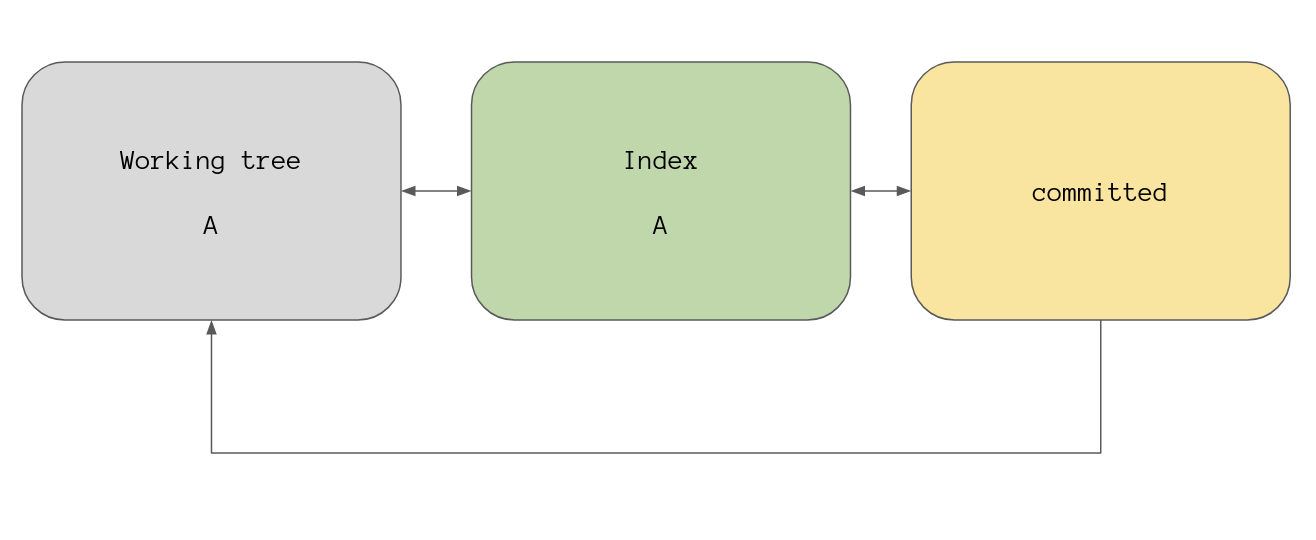

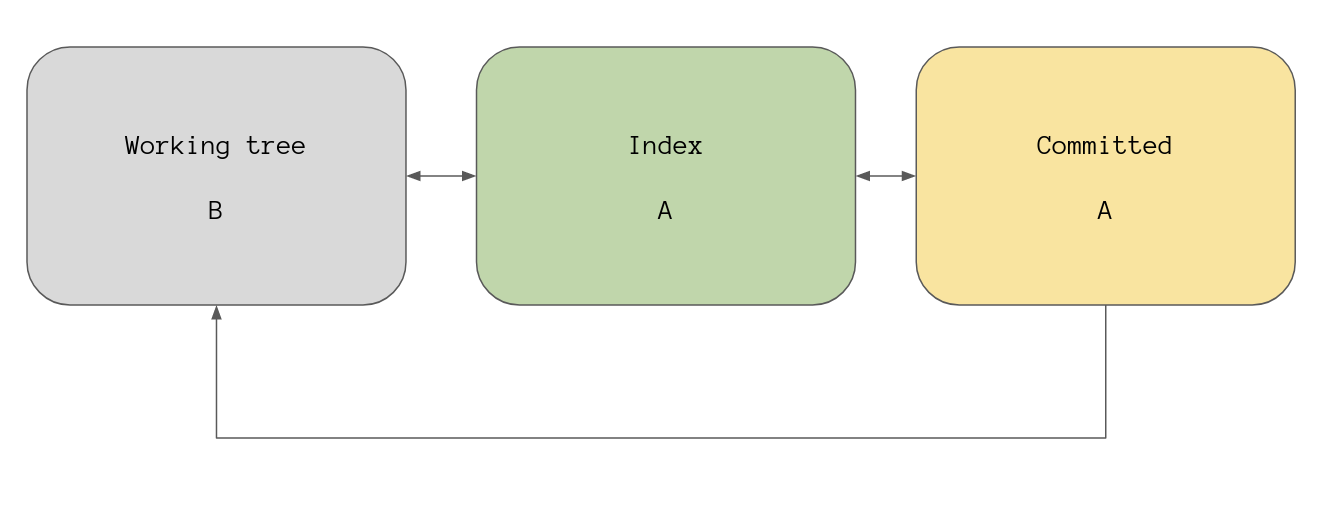

So that’s what is inside the index file right now, the version of file in

our working tree is the same as the version that’s in our index. If we consider

file to be in state A then our high level overview diagram will look like

this.

As I mentioned before git status can show us the difference between these

three stages, right now the working tree and the index version are the same:

A. There is no version of this file currently committed.

Running git status now means git will see there is something in the index that

isn’t committed so we get a "Changes to be committed" message.

> git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: file

I think it’s time we moved to the next stage and commit this bad boy.

committed

We have our staged file, all we need to do now is run git commit.

> git commit -m "commit A"

[master (root-commit) 4534c70] commit A

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 file

What happened here is git takes the contents of the index file and uses that as

the basis for a new tree object and creates a commit object with that and the

message I’ve passed in. HEAD now points to 4534c70.

This means HEAD is now pointing at the commit that contains file.

> git --no-pager show HEAD

commit 4534c709ed7a96cdbd768cc913333308dbc448f7 (HEAD -> master)

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sun Oct 11 11:21:12 2020 +0100

commit A

diff --git a/file b/file

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..5165480

--- /dev/null

+++ b/file

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+state A

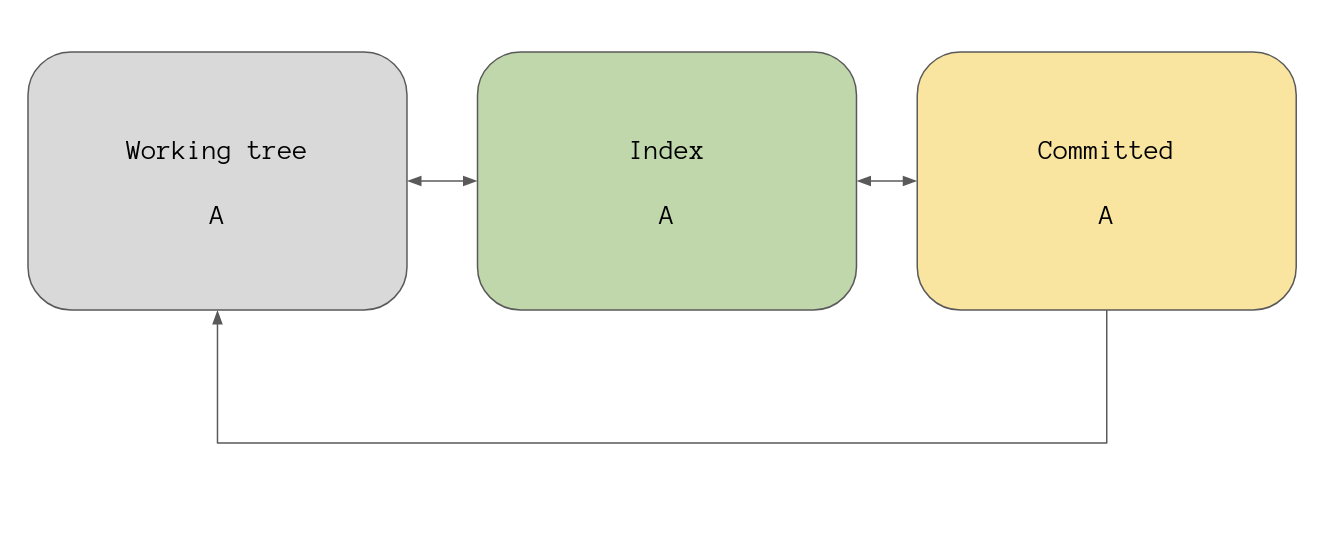

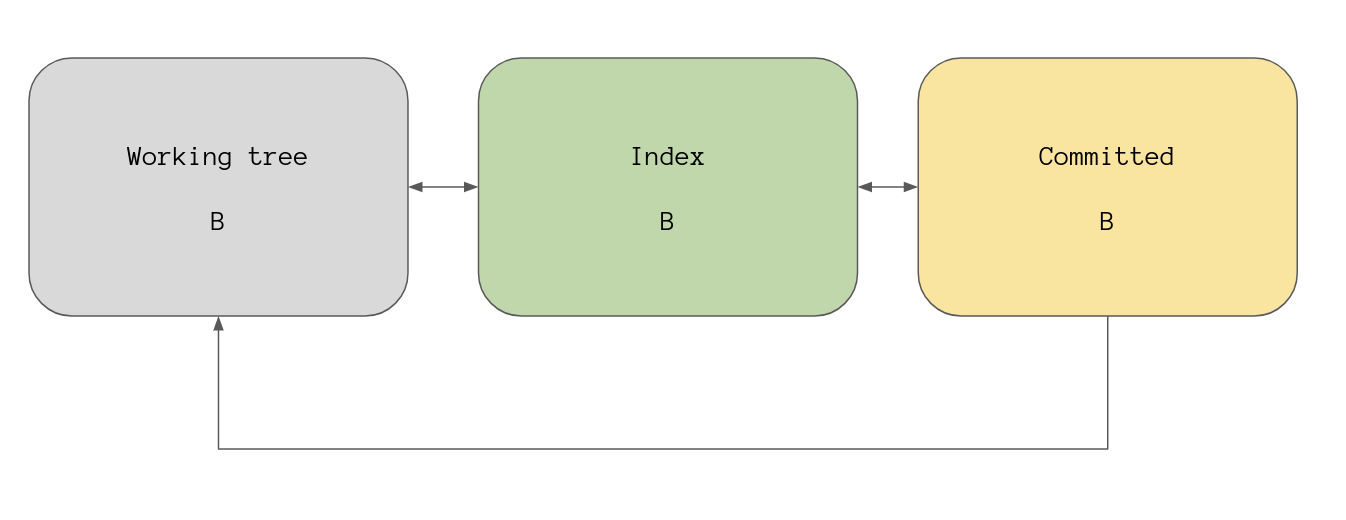

What I’ve been calling the committed stage in reality is the commit

object that’s currently being pointed to by HEAD. So our overview diagram now

looks like this:

You might think our staging area (the index file) is empty seeing as we’ve

committed our changes but that’s not true, using ls-files again we can see it

still holds a reference to file.

> git ls-files --stage -v

H 100644 51654802d7a7590f1744b7a6f6661f5fcf678799 0 file

Knowing the index file is never really empty is important because it’s how git

status is able to do what it does. Running git status will show “nothing to

commit” because:

- There are no untracked files.

- The working tree and the index currently show

filein stateA. - The index and the commit

HEADpoints to showfilein stateA.

> git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

state B

We’ve had a whistle stop tour through the three stages using a new file as our

vehicle but let’s modify file and see what git does.

> echo state B > file

> git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: file

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

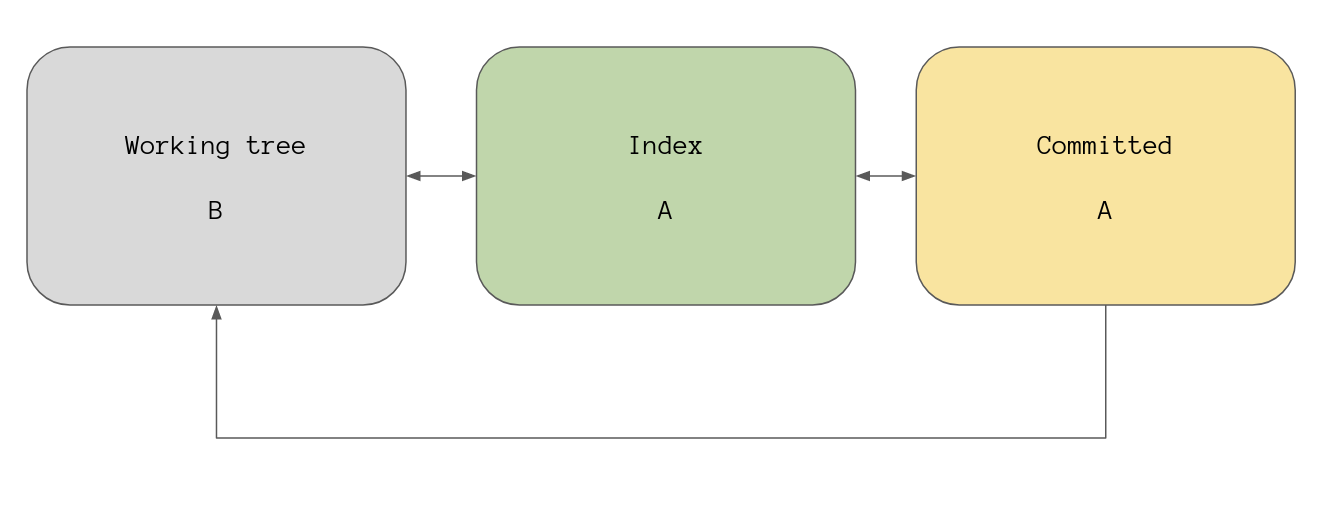

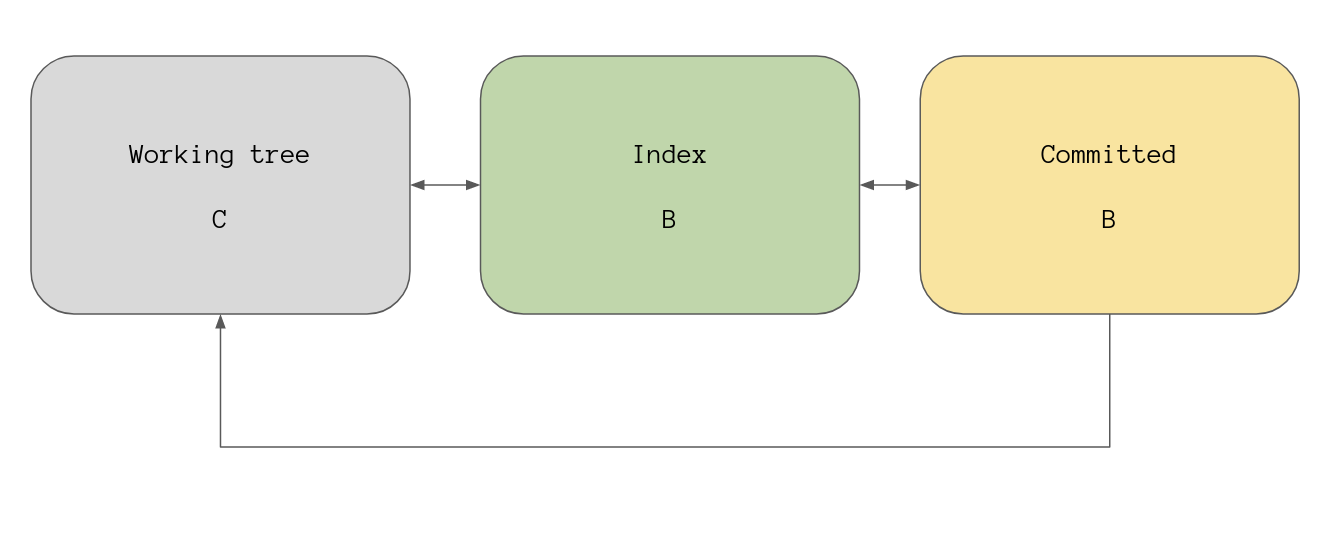

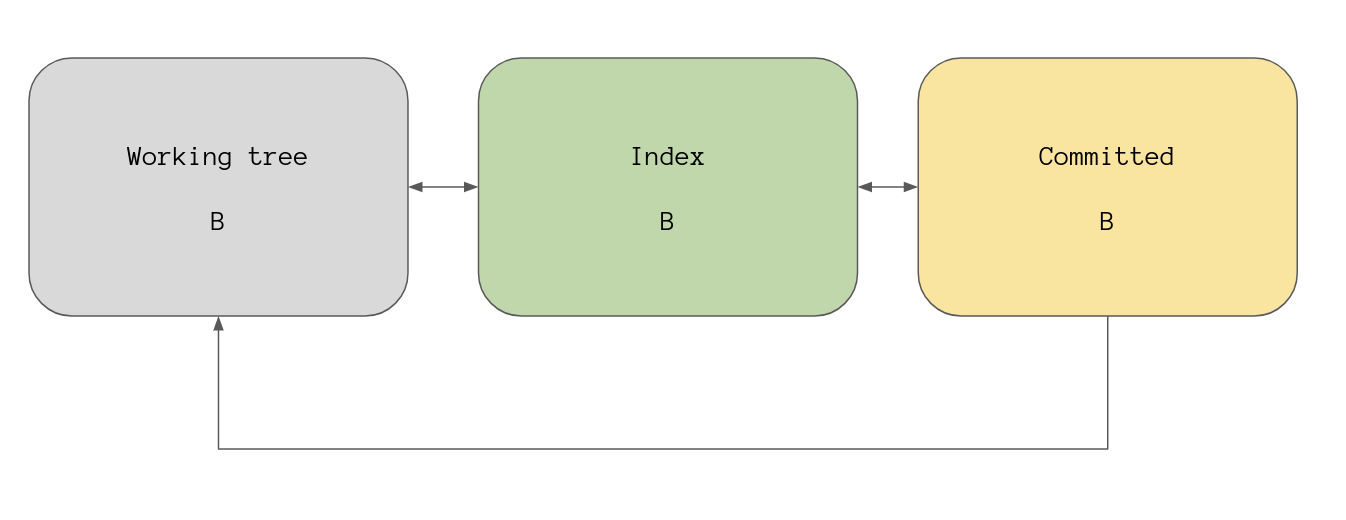

If we consider the state of file in our working tree as state B

then this is our new high level view:

git status sees there is a difference between the working tree and the index

so it shows us a message telling us file is modified.

Adding this file will update the index.

> git add file

> git ls-files --stage -v

H 100644 793840a1ed84ee1ec84a7db7b733f97c532d14c9 0 file

Notice the cached version of file in the index is different from before, the

hash has changed. git status will now show us that file is staged for commit

because although the working tree and the index now reference file in state

B the commit that HEAD is pointing to references the file in state A.

> git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: file

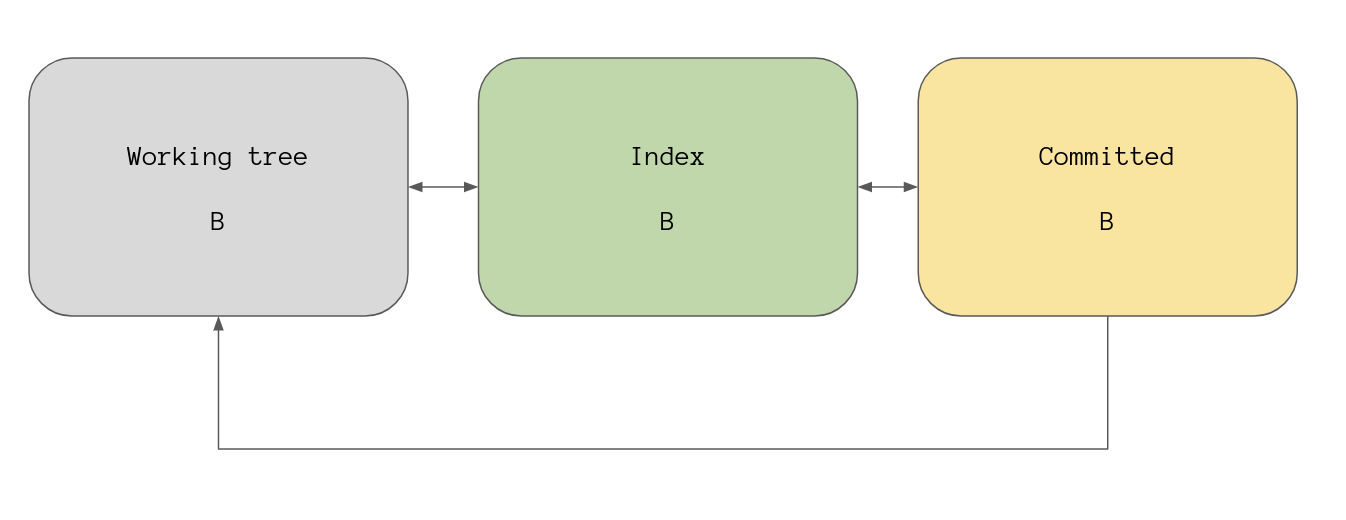

Our high level overview now looks like this:

And of course running git commit will use whatever is in the index file right

now to create a new commit object…

> git commit -m "commit B"

[master 8f2b4d2] commit B

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

…git status will show everything is up to date…

> git status

On branch master

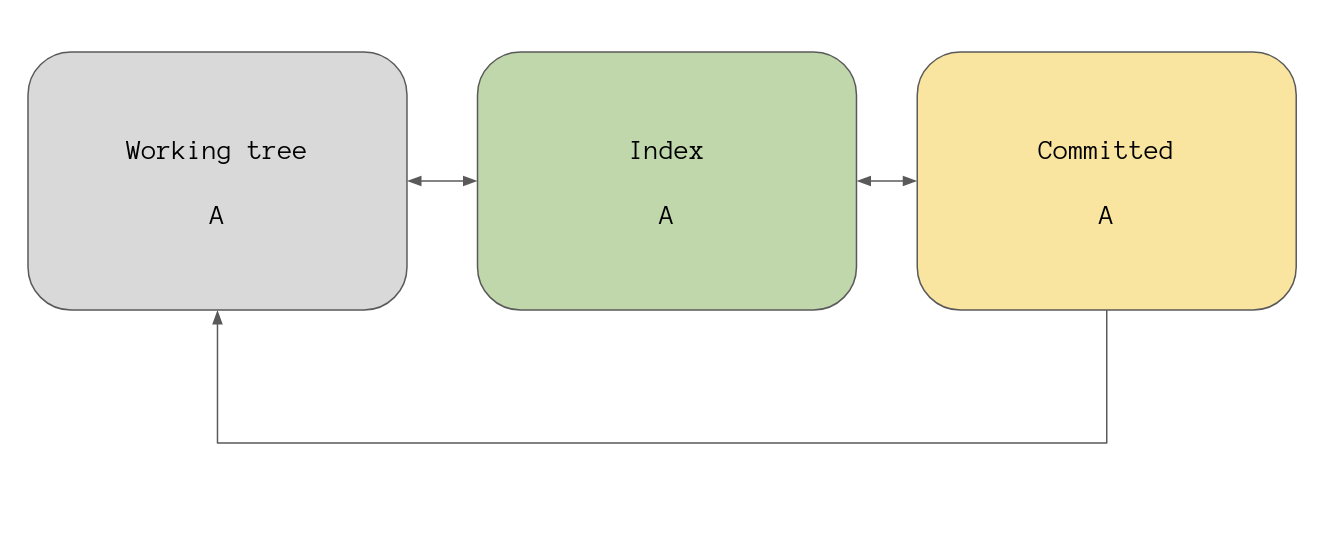

nothing to commit, working tree clean

…and our overview now shows that state B is what is seen in all three

stages.

Up until now we’ve been moving through these stages in one direction, from

left to right, but what do you do if you want to go the other way? What if you

want your committed stage to see file in state A but you want the index and

your working tree to see state B?

To answer these sorts of questions we can finally move onto talking about git reset!

git reset

git reset, according to its man page, can be used in these three ways:

git reset [-q] [<tree-ish>] [--] <paths>...

git reset (--patch | -p) [<tree-ish>] [--] [<paths>...]

git reset [--soft | --mixed [-N] | --hard | --merge | --keep] [-q] [<commit>]

I’ll go over these three uses in order.

git reset paths…

git reset [-q] [<tree-ish>] [--] <paths>...

In this form of the command git will reset the index entries for <paths>... to

whatever is in the <tree-ish> object. It does not affect the working tree or

the current branch (the committed stage in our examples).

Before I get stuck into an example here I should mention that <tree-ish> means

the command can take either a tree object, a commit object, or a tag object.

Ultimately the command wants to operate on a tree but it’ll de-reference a

commit or a tag if one is passed in to get the underlying tree object.

The brackets [] just mean the option or argument is optional so in this

instance we can just pass a path to a file and it’ll do something. If we don’t

pass a <tree-ish> object then the command defaults to HEAD.

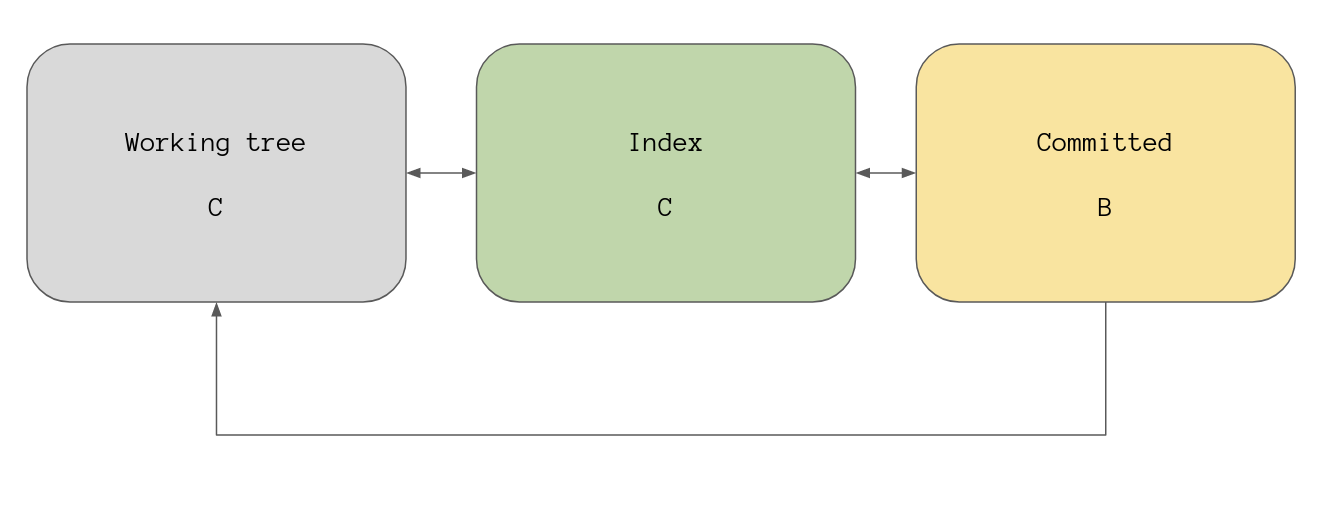

As always an example helps a lot so let’s set up the repo to look like this:

To do that I’ll just edit our file and add it to the index.

> echo state C > file

> git add file

> git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: file

As I mentioned git reset [<tree-ish>] <path> will reset the reference of <path> in our

index to reflect whatever tree we pass in or by default whatever commit HEAD points to.

That means running git reset file right now will update index to reference the

same file state that HEAD is pointing to, which is state B.

> git reset file

Unstaged changes after reset:

M file

> git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: file

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

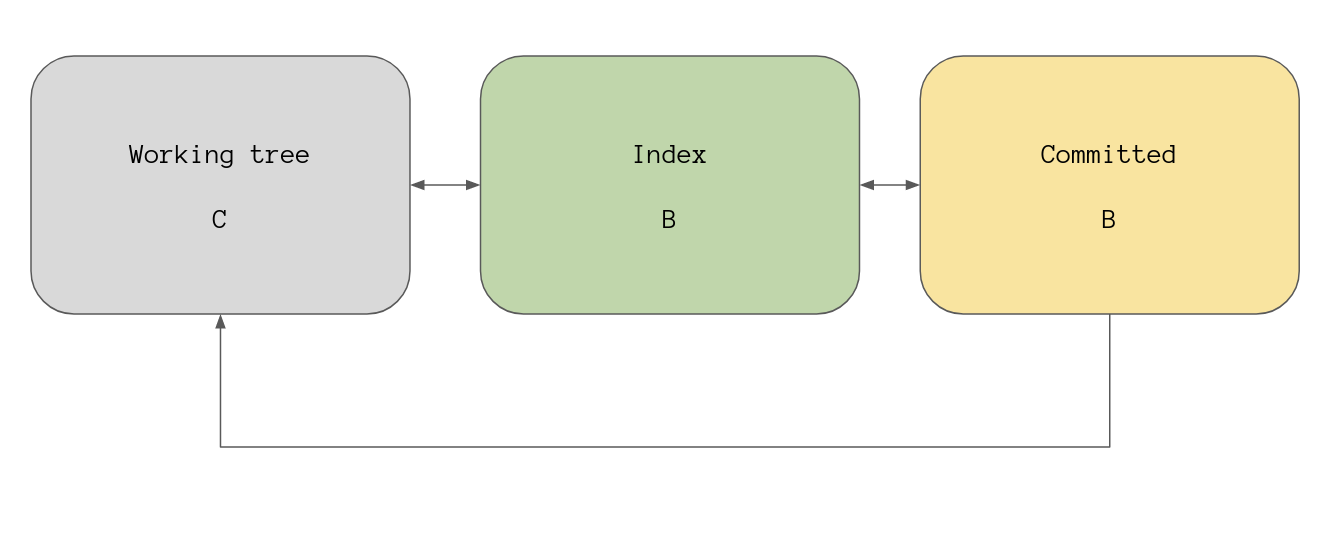

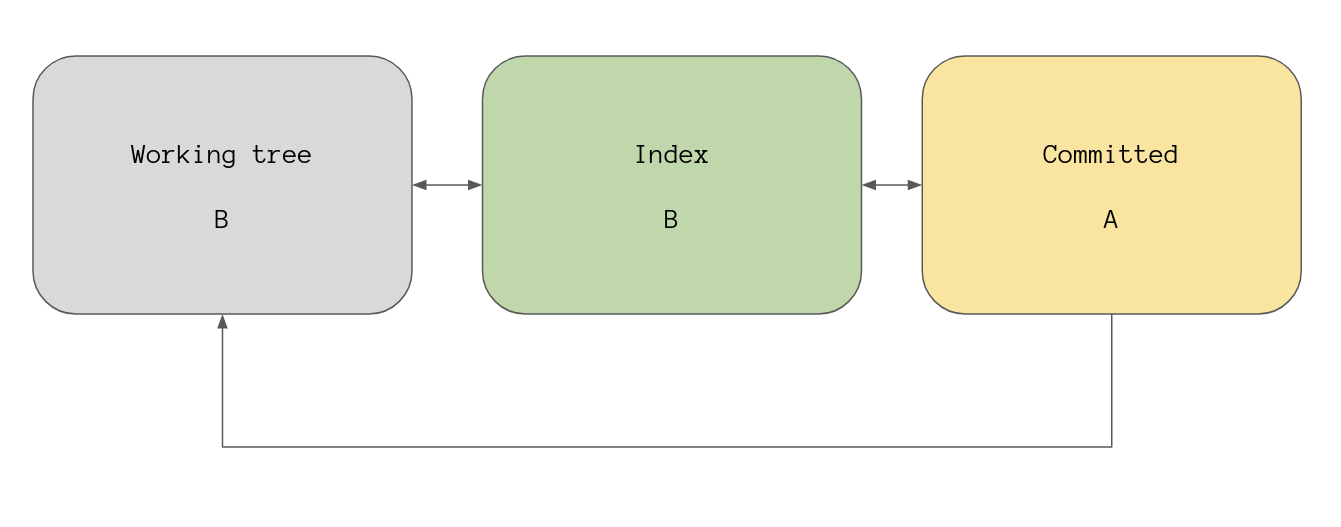

This leaves our overview looking like this:

If we instead pass a reference to commit A to the command then it will update

the index with state A for file while the working tree references state C and

HEAD references state B.

> git --no-pager log --oneline

8f2b4d2 (HEAD -> master) commit B

4534c70 commit A

> git reset 4534c70 file

Unstaged changes after reset:

M file

If everything has gone to plan then the working tree, the index, and HEAD

should all hold references to different states for file. That means running

git status now will show that we have changes not yet staged for commit as

well as staged changes ready for commit for the same file.

> git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: file

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: file

And just to prove HEAD hasn’t been moved let’s see what commit it’s pointing

at.

> git rev-parse HEAD

8f2b4d20ab48c5887cfc251a920ae9b599313c3c # <- hash for commit B

Our overview now looks like this:

In essence git reset <paths>... is how you remove a file from the staging

area, that’s pretty much the only way I use the command in this form. You can

think of it as the opposite of git add.

Actually, the current state of the repo is great as it lets me quickly go over

the second way you can use git reset and that’s using the --patch option.

git reset –patch

git reset (--patch | -p) [<tree-ish>] [--] [<paths>...]

A few of the git commands take a --patch option, for example git add which I

wrote a short post on a while ago. Like git add the -p option allows you to

interactively select hunks from files that you want to update in your index

file, AKA unstage those changes.

This is exactly the same as the previous way to use the command except it’s

interactive and you don’t have to specify <paths>... either. Without a tree or

a path the command will ask you for each hunk in the index if you want to reset

it to what HEAD can see for the file.

Remember that the index is currently holding a reference to file in state A

and HEAD is pointing at commit B, the following should bring the index back

inline with HEAD.

> git reset -p

diff --git a/file b/file

index 793840a..5165480 100644

--- a/file

+++ b/file

@@ -1 +1 @@

-state B

+state A

Unstage this hunk [y,n,q,a,d,e,?]? y

> git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: file

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

> cat file

state C

This has left our overview looking like this again:

That’s all I want to say about --patch so let’s tackle the last way you can

use git reset.

git reset –mode

git reset [<mode>] [<commit>]

This way of using the command will require a little more explanation that the

other two ways we just went over, and that’s because this version will update

HEAD to point to whatever <commit> you pass in. If you don’t pass a

<commit> then the commit that HEAD is pointing to is used.

On top of the whole commit malarkey you can pass a <mode> option, and you get

to choose from these:

- –soft

- –mixed

- –hard

- –merge

- –keep

If you don’t choose a mode then --mixed is the default.

Now I’ll be honest I had no idea --merge and --keep existed until I read the

man page for git-reset for this post. I am going to explain the fuck out of

the first three but I’ll leave the last two for you to read up on by yourself.

The thing to keep in mind when resetting to a commit is that HEAD is always

moved, you specify a mode to determine what happens with the index and the

working tree.

–soft

git reset --soft [<commit>]

The soft mode allows you to update the commit that HEAD points to while

leaving the index and the working tree completely untouched.

To demonstrate let’s say the repo is at commit B and the working tree, the

index, and HEAD all see file in state B.

Running git reset --soft 4534c70 to reset HEAD to point at commit A should

result in this view of the world.

> git reset --soft 4534c70

> git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: file

> cat file

state B

As expected git status is saying we have staged commits because our working

tree and index see file in state B whereas HEAD is pointing at commit A

and sees the file in state A. And this is what HEAD is pointing to:

> git --no-pager log --oneline

4534c70 (HEAD -> master) commit A

Here is a wee tip for you, when you run a command in git that moves HEAD git

will create ORIG_HEAD that points to the commit that HEAD was pointing to before

you did the action.

That means we can move HEAD back to commit B by running git reset

ORIG_HEAD.

> git reset ORIG_HEAD

> git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Seeing as all of our stages are now referencing the file in state B then

there’s nothing for git status to report.

–mixed

git reset --mixed [<commit>]

This option is the default mode that’s used if you don’t pass a mode option, so all of these versions do the same thing:

git resetgit reset HEADgit reset --mixedgit reset --mixed HEAD

Like --soft this command will update HEAD to point at <commit> except this

time the index is updated to reflect <commit> and the working tree is left

untouched.

As a reminder here is our view of the world as it stands right now:

Running git reset --mixed 4534c70 to point HEAD at commit A should also

update the index.

> git reset --mixed 4534c70

Unstaged changes after reset:

M file

> git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: file

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

git status confirms that index was indeed updated to reflect commit A and

shows that we have a modified file in our working tree because our working tree

is showing file in state B.

This is our view of the world now:

Let’s reset using git reset ORIG_HEAD and have a look at the next option.

–hard

git reset --hard [<commit>]

If --soft left the index and the working tree alone, and --mixed updated the

index and left the working tree alone, then it makes sense that --hard would

be the option that updates everything.

Running this command will reset all of our stages to reflect <commit>.

Currently every stage sees file in state B

Let’s reset every stage to commit A which has file in state A.

> git reset --hard 4534c70

HEAD is now at 4534c70 commit A

> git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git status is reporting no changes because our working tree, our index, and

HEAD are all seeing file in state A.

This mode is very handy if you need to completely blow away a bunch of commits and you don’t care about the changes those commits had made.

fin

Well shit is that it? No of course not there’s plenty more in the git-reset

man page for you to read! Everything I’ve just explained should cover 99%

of the things you will ever want to do with git reset, at least now we

understand what the hell is going on.

Go read the docs for git reset and don’t be scared. I believe in you.