Where Did Vim Come From?

12 Jul 2020 | categories: blog

prev: Ruby: Blocks, Procs, and Lambdas | next: How Git Works

For a lot of people vim is the editor they use every single day, for some people they only interact with it when using git because it’s the default editor on their system. For me I used to be in the latter group until last year when I made the plunge and now I sit firmly in the former.

Vim is an interesting piece of software with a steep learning curve, but what I find most interesting about it is its family tree. Vim didn’t just fall out of Bram Moolenaar’s head one sunny afternoon, it was an iteration on an already existing piece of software.

I find the history interesting enough that I would like to walk through how this ubiquitous text editor came to be, so get your coat and let’s head on back to the 1960s.

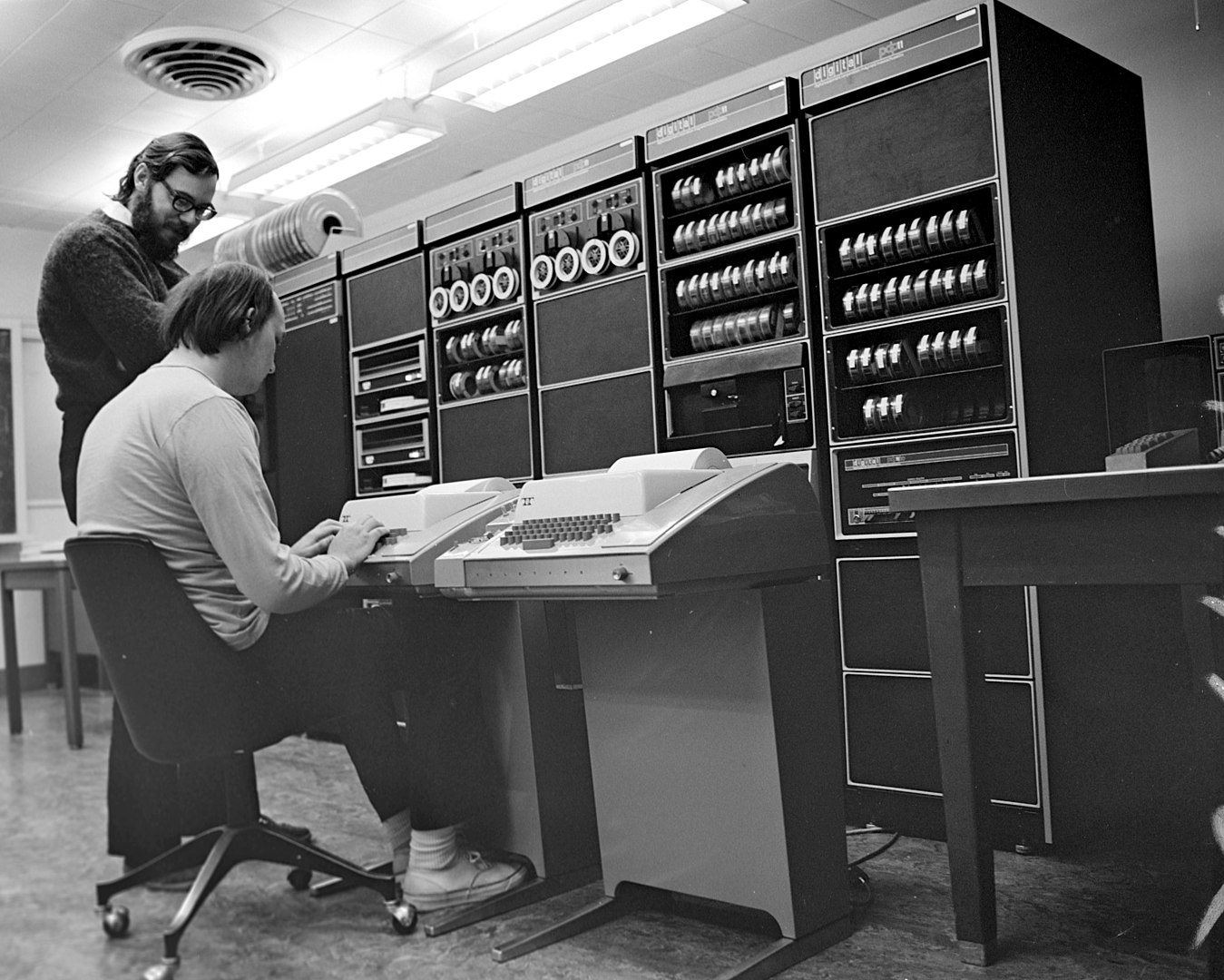

unix development

Back in 1969 the development of the Unix

operating system had begun at Bell

Labs, and amongst those developing the

system was an engineer called Ken

Thompson. Ken was, in my eyes, some

sort of wizard. Over his life time he has created or had a hand in creating many

useful things such as grep and the

Go.

By Peter Hamer - Ken

Thompson (sitting) and Dennis Ritchie at PDP-11

Uploaded by Magnus Manske, CC BY-SA 2.0, Link

As you can see in the image above there were no CRT displays kicking around,

they had to do all of their programming using teletype printers, this meant any

input or output would be line by line. Ken Thompson was used to using a line

editor from university called

qed which stands for

Quick Editor. He had reimplemented qed for a few systems since then, in fact

these versions of his are notable due to the fact they were the first to

implement regular

expressions, but for Unix he

decided to write his own version of qed which he called

ed.

line editors

ed is still found on computers today, it is known as the “standard editor”, so

I would like to briefly depart from the history lesson to give you an overview

look at how ed works. Not only is this handy to know but I want to show you

just how involved editing text is with a line editor.

Δ ed

i

hi there

.

w my_file

9

q

Δ cat my_file

hi there

Starting at the top I have entered the command ed which starts with a blank

buffer, nice and simple so far. ed is a modal editor so on line two when I

enter the application I am sitting in “command mode”, I enter the i command to

enter “insert mode”, this means anything I type after this will be entered into

my buffer on the line that I am currently at. I type the string “hi there”

followed by a single dot, this dot tells ed I have finished editing and would

like to return to command mode.

I then issue the command w followed by a file name “my_file”, ed obliges and

saves the buffer to a file then tells me how many characters that were written

(9 which includes the newline). Then I issue the q command to exit ed and

I’m back in the shell where I print out the contents of my file.

ed’s other tricks

Being able to write text to a file is fine, but you know when you’re editing code you want to be able to jump around, make edits, move text, all of that good stuff.

For this section I have a file called food with this text in it.

dear god I love pizza

is there anything more joyous than melted cheese

circular food clearly came from the heavens

pizza is the bomb

I’ll also split the input/output into smaller sections to talk about it as we go, it’s easier to follow that way.

viewing lines

Δ ed food

133

P

I start ed by giving it the name of the file I want to edit and it loads it

into a buffer for me then tells me there’s 133 characters. I use the P command

to turn on the prompt which adds an asterisk so you can see which lines are

command prompts and which are output from ed.

*.=

4

When you load up a buffer you are placed at the final line and your current line

can be referred to by a dot, so any command that expects a line number will also

accept a dot (the last line is represented by $). The = command prints out

the line number so I run .= to show you our current position is at the end of

the buffer.

*1

dear god I love pizza

*3

circular food clearly came from the heavens

*1,3p

dear god I love pizza

is there anything more joyous than melted cheese

circular food clearly came from the heavens

Entering a number and hitting enter will move you to that line and print it

because p (print) is the default command, so if no command is specified then

it’ll assume p. I show you lines 1 and 3, then I print a range of lines with

the m,n syntax. m being the first line through to n inclusive.

*g/pizza/p

dear god I love pizza

pizza is the bomb

The g/pizza/p command is made up of g, /pizza/, and p. The g command

means globally do something (i.e. for each line), then the text between the

forward slashes is a regular expression, and finally p prints. In other words

for each line, if you see the word pizza in it I would like to print the line.

Does this functionality seem familiar? If we shorten “regular expression” down

to “re” then you get g/re/p. This was so handy Ken Thompson pulled it out of

ed and made it a dedicated command for searching for text in files and called it

grep.

*q

Δ

And for the sake of completion I exit ed with the q command.

some edits

To wrap up this detour I’ll quickly show some edits.

Δ ed food

133

P

*n

4 pizza is the bomb

As usual we fire up ed and it graciously tells us the character count, then

whack it in prompt mode to help differentiate the input/output. n will print

out the line with the line number and it defaults to .n which is your current

line.

*a

too much probably isn't a great idea though

.

a means “append”, so we add a new line to the end of the buffer and as usual a

dot on its own means we are finished inputting our text.

*1,$s/pizza/pie/g

*1,$p

dear god I love pie

is there anything more joyous than melted cheese

circular food clearly came from the heavens

pie is the bomb

too much probably isn't a great idea though

Then the next line we make use of the incredibly useful s command which is

used for substitutions. 1,$s/pizza/pie/g means from line 1 to the end of

the buffer ($) I want to substitute the regular expression pizza with the

text pie. I’ve tacked on a g at the end which again means global but, because

s works on single lines, g in this context means change every instance of

pizza found on the line, otherwise only the first occurrence of “pizza” would

be affected.

fuck me that was effort

Yes, that is a lot of work. And if you were using a teletype printer like Ken was you’d have to wait until the printer spat out the output. Slow, laborious, not to mention the syntax is quite dense, but it worked. Imagine writing an entire operating system using it.

On that note, you would do well reading the ed

manual or at least

knowing where to find it because who knows perhaps ed will be the only thing

you have on a server some day, it could save your bacon.

There is a lot more to ed, I barely scratched the surface there with my brief

overview. I’m sure if you saw someone who understood it inside out (perhaps

someone who wrote ed, like Ken Thompson) you might say you’d need to be some

sort of God to understand it at all.

em

Someone who certainly felt the same way about ed was a guy called George

Coulouris,

in the autumn of 1975 he extended ed enabling his new software to make use of

these fancy new video terminals that the university he was attending had

recently acquired. em would allow you to see parts of the file you were

editing.

He named his creation em which is short for ed for mortals. Apparently Ken

Thompson had visited George’s university once when George was developing em and

Ken had this to say:

“yeah, I’ve seen editors like that, but I don’t feel a need for them, I don’t want to see the state of the file when I’m editing”.

Alright Ken you mentalist.

ex

In 1976 George Coulouris spent the summer as a visitor in the Computer Science

department at Berkeley where he brought his em software with him, after all

they had teletype terminals so why not. During this trip he met a man called

Bill Joy and George showed him em,

and Bill was certainly impressed by it.

The only problem with em was that it would be very CPU intensive, especially

if it was loaded onto a mainframe that would be used by multiple users. Bill

took a copy of George’s em before George left Berkeley and began working with

a chap called Chuck Haley on the source code, trying to improve it to make it

less resource intensive. This led to the creation of

ex which stands for

EXtended.

Version 1.1 of ex made it onto Berkeley Software Distribution of Unix (BSD) in

1978.

tool legacy

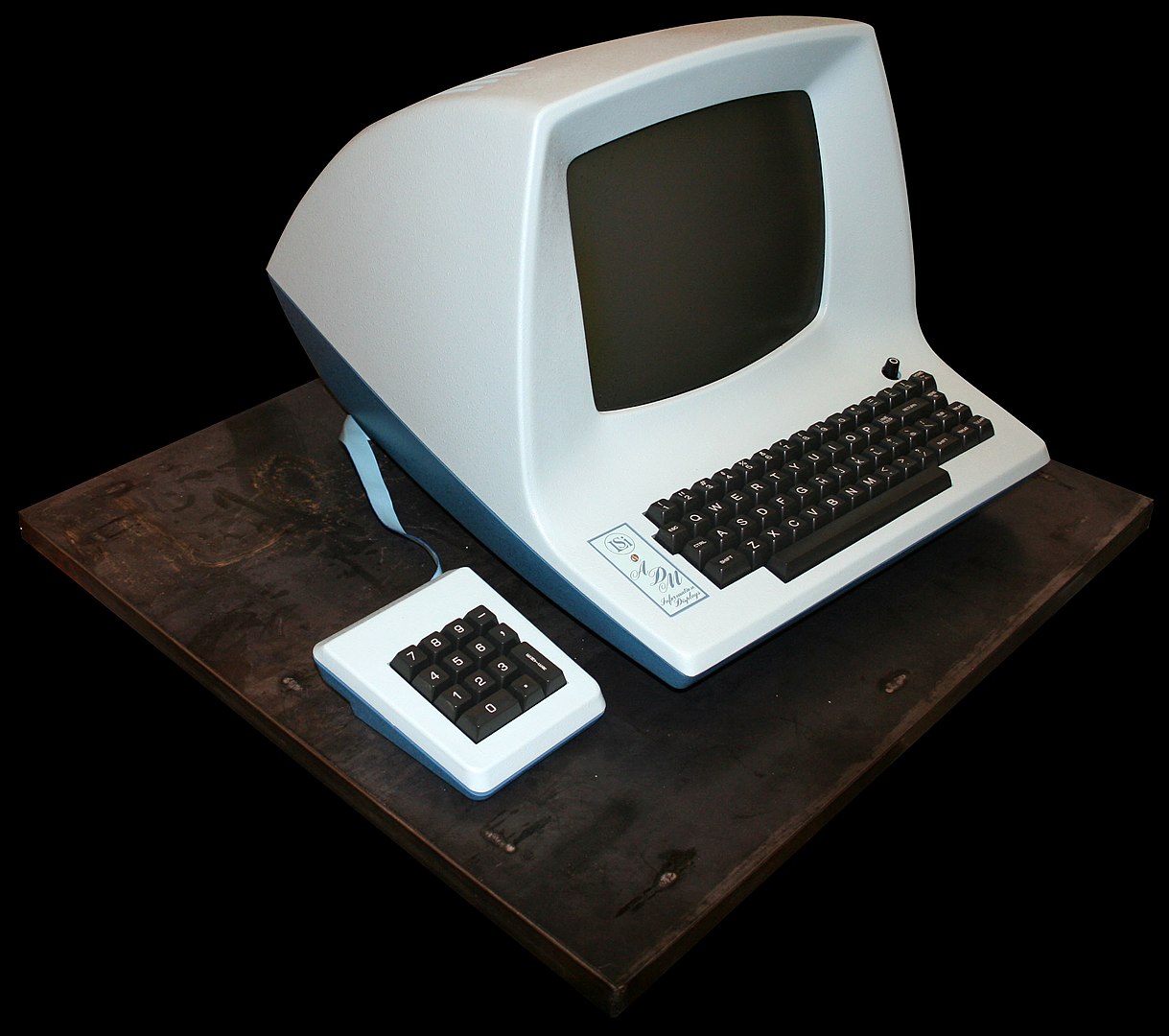

Bill Joy used a computer called the

ADM-A3 to write the code for ex, and

the computer had a profound affect on it. The reason being that it had a

particular keyboard layout which drove many of the decisions he made when it

came to deciding which symbols/keys to use for commands.

By Chris Jacobs - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Pictures are lovely, the one above is nice, but what I’m interested in showing you is the keyboard layout, so let’s see a diagram.

By No machine-readable author provided. StuartBrady assumed (based on copyright claims). - No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

There are a few things that are different here than our modern keyboard layout so I’ll bullet point them:

- The escape key is where you would usually find the tab key

- The control key is where you would usually find the caps lock

- The

:symbol doesn’t need you to press shift - The arrow keys are on the home row

- The

~symbol is on theHOMEkey.

The first four will interest people who use vim while the last one is just

interesting in itself, the computer was so influential during that time that

it’s the reason we can write ~/file_name as a substitute for

$HOME/file_name today.

vi

Now, ex is itself a line editor but it did have a command you could enter to

go into a visual mode, and that was :visual or :vi for short. They found

over time that people were entering ex and the first thing they were

doing was entering :vi to switch to visual mode. So in ex 2.0, which was

released on BSD in 1979, vi was created as

a hard link to ex which put a user directly into visual mode. In reality vi

and ex aren’t two different things, vi is ex.

Bill Joy worked as the lead developer on the project up until version 2.7, and he continued to make occasional contributions to the project up until version 3.5 in 1980.

Mary Ann Horton took the baton

and assumed responsibility for vi adding support for things like arrow keys,

macros, and improving the performance. vi was improved upon over the coming

years, but because it was initially built upon ed it meant ex and vi could

not be distributed without an AT&T source license (due to ed being developed

at Bell Labs). People wanted free alternatives and as a result clones of vi

began popping up, in 1987 a dude called Tim Thompson wrote a clone of vi for

the Atari ST which he called ST Editor

for VI Enthusiasts, or

STEVIE for short.

Vim

Tim Thompson posted the C source code for this editor on a newsgroup in 1987 and it was ported to Unix, OS/2, and Amiga by someone called Tony Andrews. And it is here where Braam Moolenaar got the source code of this STEVIE port for his Amiga which he started tinkering with to create his own editor. Braam released the first public version of his creation in 1991 which he called “Vim”, this stood for “Vi IMatation” but he later changed to “Vi IMproved” in 1993.

what a bunch of nerds

As is always the case with computers and software there is a rich history full

of complete dorks building things because they love what they do. No one told

Ken Thompson to create ed, no one put a gun to George Coulouris’s head and

told him to write em, no one forced Bill Joy to improve it and create ex, I

dare say Tim Thompson created STEVIE because he wanted to, was Tony Andrews

coerced into making those ports of STEVIE? Hard to say but I’m not putting

money on it. Then we come to Braam Moolenaar who, like everyone else, just

created vim because he wanted to.

Imagine what state the world would be in if people didn’t create things for free and give them away. Imagine what kind of world we would have if there wasn’t an abundance of dorks everywhere. Long live dorks.