How Git Works

19 Jul 2020 | categories: blog

prev: Where Did Vim Come From? | next: How Containers Work

For the longest time I was scared of Git, I had a surface level understanding at best and even that is being generous. I could do all the essential things like create commits and push branches, but if anything went wrong I would have no idea what was going on and would likely just delete my branch and start again hoping whatever error I ran into wouldn’t happen again.

This is no way to work, we shouldn’t be scared of the tools we use every day. In fact just understanding them better helps us be more productive, I’ve written a few posts in the past about various git features but those features, whilst great to know about, are pretty meaningless without a good mental model of how git works.

I’m going to try my best to explain how git stores data and what exactly happens when you use normal git commands, also known as porcelain commands, by introducing you to some lower level plumbing commands which we will use to achieve exactly the same results. After that I’ll go over how git keeps track of branches, also known as references. Then I’ll finish up by showing how git tries to efficiently store your data using compression.

A word of warning this post will no doubt end up being quite long but I’m hoping the detail I go into will be of use for you. Before getting stuck into some command line action I think going over how git is different to other version control systems would be beneficial. Let’s get started.

how is git different

Like most people I learnt how to use git because it is the de facto version control system (VCS) for most projects, but there are other older VCSs available like Concurrent Versions System (CVS) and Subversion (SVN), but it seems git has become so popular that for a lot of people it’s the only VCS they know. Compared to SVN and CVS, git is different in two big ways.

centralized and decentralized systems

SVN and CVS are “centralized” and use a client-server model, meaning there is a central server which holds the single source of truth for a project and people will push changes to and pull new changes from the server.

Git and other VCSs like Mercurial, on the other hand, are “distributed” meaning everyone on a project will have their own version of the repository on their machine. The local repository holds the entire history of the project so you don’t need to be online to make changes to your work, you can work purely on your local repository and push changes upstream later. This upstream repository can be any repository though, you could push to one on github, or you could set up your own git server, or you could even push to a team mate’s repository if you’ve got access to their machine.

content management

Git is described in its man pages as “the stupid content tracker” which perfectly sums up what it is, it’s a content-addressable filesystem which is just a fancy way of saying it stores files based on their content and not their location. You can think of it as a key-value store, you store a file and you get back a unique key, you can then fetch that data later using the same key.

The main thing you need to keep in mind is the fact git is content-addressable, the following examples will shed a little light on what that actually means.

the .git folder

I have a directory that isn’t yet a git repository, it’s completely empty.

/tmp/example » ls -al

total 164

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:42 .

drwxrwxrwt 127 root root 159744 Jul 18 09:42 ..

If I run git init then git will create a new .git folder for me in the

current directory, this .git folder is your repository.

/tmp/example » git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /tmp/example/.git/

/tmp/example [master] » ls -al

total 168

drwxr-x--- 3 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 .

drwxrwxrwt 127 root root 159744 Jul 18 09:43 ..

drwxr-x--- 5 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 .git

/tmp/example [master] »

When you run git clone git@github.com:user/exciting-project all git does is

pull down the .git folder from the remote repository then populate your

working directory with the files from the most recently commit on the master

branch.

the different files

Let’s have a look inside the newly created .git folder and see what we have to

work with

/tmp/example [master] » ls -al .git

total 28

drwxr-x--- 5 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:48 .

drwxr-x--- 3 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 ..

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 92 Jul 18 09:43 config

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 23 Jul 18 09:43 HEAD

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 hooks

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 objects

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 refs

The config file is the configuration for this local repository, you can also

have a system-wide config that lives in /etc/gitconfig, a “global” config that

lives in your home directory ~/.gitconfig, and a worktree specific config

which is the one we see here .git/config. Git looks for these config files in

that order, meaning you can have an option set in your global config but

overwrite it on a per repository basis using your worktree, or local, config.

The HEAD file is a pointer to the object you’re currently looking at in your

working directory, ideally this will be a branch which then points to a commit

but you can point HEAD at specific commits which is when you get the scary

DETACHED_HEAD warnings. I’ll come back to this topic later.

hooks is a directory for small scripts that git will be run before/after specific

events, e.g. before pushing a branch.

refs is a directory which holds your references, these are things like

branches and tags. I’ll go into more detail on this directory later.

objects is the directory that git uses as its “database”, and objects are the

first things I would like to talk about.

object directory

If we look inside the objects directory we will find some subdirectories

/tmp/example [master] » ls -al .git/objects

total 16

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 .

drwxr-x--- 5 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 10:07 ..

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 info

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 pack

But right now there are no files in there

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

/tmp/example [master] »

Let’s try adding an object, and to do that we need to create a file in our project.

/tmp/example [master] » vim my_file.txt

/tmp/example [master] » cat my_file.txt

hello there

/tmp/example [master] » git hash-object -w my_file.txt

c7c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

I’ve created a new file called my_file.txt and added some text to it, then I

have run the plumbing command hash-object with the -w option which means

hash the contents of the file and write the object to our database. Git does

what we ask and returns the hash for the object. This hash is created using the

SHA1 hashing algorithm and will change based on the contents of the file, if you

were to copy the commands I’ve used so far you should get exactly the same hash

back. Changing even one character of the file would result in a drastically

different hash, you can think of this hash as a unique finger print that

identifies the content of the file.

If we look for files in .git/objects again we should find the object that was

just created

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

Git has taken the hashed file and stored it in the objects directory using the

first two characters of the hash c7 as the name of a new subdirectory and then

the other 38 characters as the name of the file. The type of object that is

created when you hash a file is called a blob.

looking at objects

Git has a few plumbing commands that let you look at objects, if we want to see

the contents of our newly created blob then we can use cat-file with the -p

option to print the file contents.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p c7c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

hello there

We can also see what type of object it is by using the -t command.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -t c7c7da

blob

Notice we can use an abbreviated hash anywhere git expects a hash, you need to provide at least 5 characters and git can usually find what you’re after.

Now you might be thinking that an object stores the file contents as is, the

-p option from before certainly would’ve reinforced that belief, but if we

cat the actual file you can see that’s not the case. We get back gibberish.

/tmp/example [master] » cat .git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

xKOR04bHW(H-JCy%

Git compresses file contents using zlib and stores that instead, then

decompresses objects when you need to use them in your working directory. This

is part of the reason git is able to work on massive repositories with thousands

of files without your project history using all of the memory on your drive.

creating a new version of a file

We have the first version of my_file.txt saved in our object database, let’s

create a new version by appending some text to the file.

/tmp/example [master] » echo "how are you?" >> my_file.txt

/tmp/example [master] » git hash-object -w my_file.txt

35feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2

I’ve added a new line to the file, asked git to hash and store the resulting

object. As you can see we have gotten a completely different hash back, and if

we look inside the objects directory again you can see we now have two objects,

our previous version and this new one.

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

.git/objects/35/feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2

For the sake of complete transparency let’s print out the contents of this object to show that git has stored the entire contents of the file. Later I will explain how git gets around storing entire versions of files to save even more space.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p 35feec

hello there

how are you?

So far we have been looking at blob objects, but you might have noticed that the git hasn’t stored the name of the file anywhere. This is intentional, a blob object just represents content so if you have 500 files all with the same content you only need one blob object, this is much more space efficient. How does git remember what content certain files should have then?

tree objects

A tree object is the object that git uses to match blob objects to file names, you can think of it as a representation of a directory.

Git creates tree objects from your index, also known as the staging area, so

let’s use a new plumbing command called update-index to add some files to our

index. Before doing so I’m going to create a new file called

my_second_file.txt, the contents of which aren’t important.

/tmp/example [master] » vim my_second_file.txt

/tmp/example [master] » git update-index --add my_second_file.txt

/tmp/example [master] » git update-index --add my_file.txt

It’s worth noting here that the update-index plumbing command will hash the

file for us and insert it into the objects directory automatically. We should

have three blobs in our objects directory, 2 versions of my_file.txt and a new

one for my_second_file.txt.

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

.git/objects/5e/86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214

.git/objects/35/feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2

And if we look inside the .git folder again you will see a new index file

has been created for us, this is what is updated when you stage files, we just

happened to use a plumbing command to achieve the same result.

/tmp/example [master] » ls -l .git

total 24

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 92 Jul 18 09:43 config

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 23 Jul 18 09:43 HEAD

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 hooks

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 200 Jul 18 10:55 index

drwxr-x--- 7 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 10:55 objects

drwxr-x--- 4 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 09:43 refs

Running the git status porcelain command will tell us that we do indeed have

some files staged in our index file.

/tmp/example [master] » git status -sb

## No commits yet on master

A my_file.txt

A my_second_file.txt

We can use a plumbing command called ls-files to inspect the contents of the

index too, this will show us the file contains hashes of blob objects and

the file names, as well as some other information like file permissions.

/tmp/example [master] » git ls-files --stage

100644 35feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2 0 my_file.txt

100644 5e86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214 0 my_second_file.txt

As I mentioned before, tree objects are created based on what is in index so

let’s take what we have in our index and create a tree object, to do that we use

the write-tree plumbing command. The command will create the tree object and

spit out the hash for it, this object is then saved in the database just like

blobs.

/tmp/example [master] » git write-tree

7efe94e736bc17a55fda2b8b5bc6e125c1454ea4

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

.git/objects/5e/86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214

.git/objects/7e/fe94e736bc17a55fda2b8b5bc6e125c1454ea4

.git/objects/35/feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2

contents of a tree object

Cool, we have a tree object now but what the hell is it? They make a little more

sense when you see what they consist of. Like we did with the blob objects we

can print out the contents of a tree object using cat-file, passing -t first

to show you the object type is tree.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -t 7efe94

tree

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p 7efe94

100644 blob 35feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2 my_file.txt

100644 blob 5e86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214 my_second_file.txt

This tree object is quite simple, it says “in the root of the project we have two files, and here are the hashes of blob objects, here are the file names along with the file permissions”.

Seeing as the type of the object is noted down it is reasonable to assume that trees can reference other trees, and this is exactly right. In fact this is how git is able to keep track of the entire file system in your repository.

tree within a tree

To demonstrate that last point I’ve added a subdirectory in the repository with

some files, the contents of which are not important. Note the tree command I

use here isn’t a git command.

/tmp/example [master] » tree

.

├── my_file.txt

├── my_second_file.txt

└── subdir

├── bar.txt

└── foo.txt

1 directory, 4 files

I go through the same steps to add the new files to the index like we did previously and then I create a new tree.

/tmp/example [master] » git update-index --add subdir/*

/tmp/example [master] » git write-tree

da77a56b7a85f94f957b97ba3bc10e089e3daea0

Printing that tree object out now and we can see a new line has been added, only this time it’s a tree object. It shows that at the root of the project we have two files and another tree object representing a sub directory.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p da77a5

100644 blob 35feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2 my_file.txt

100644 blob 5e86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214 my_second_file.txt

040000 tree 80742180d72a4a91376be94367991f9b498e72f7 subdir

If we print out the tree 807421 we will see the files foo.txt and bar.txt

that reside in the subdirectory.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p 807421

100644 blob 9baf85eb7aa8e3dda46b3388b4ad32841cff85fa bar.txt

100644 blob ce013625030ba8dba906f756967f9e9ca394464a foo.txt

commit object

Right now we have some blobs and trees in our database however we have no idea

who created these objects, the time they were created, nor why they were

created. Enter commit objects.

commit objects are created from tree objects, let’s create one using the most

recent tree we created da77a5 and the plumbing command commit-tree.

/tmp/example [master] » echo "Initial commit" | git commit-tree da77a5

86eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341

commit-tree needs a commit message so I provide one through a pipe, as usual git

creates the commit object then gives us back the hash for that object.

It goes without saying that the object is also saved in .git/objects. A commit

object is just like any other object and the hash is based on its contents, this

is why changing a commit message will give you a completely different hash.

Let’s look inside the commit that was just created.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p 86eb47

tree da77a56b7a85f94f957b97ba3bc10e089e3daea0

author Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev> 1595067822 +0100

committer Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev> 1595067822 +0100

Initial commit

The commit object points to the tree object da77a5 and stores some information

on who created the commit, the time they created it, and a nice message telling

us what the change is.

how far we’ve come

Before I continue let’s just recap what we have managed to achieve using only plumbing commands:

- created blob objects

- updated our index

- created a tree object that references blob and tree objects

- created a commit object that references the tree object

This pretty much what happens when we run:

git add <files>git commit -m "Initial commit"

The porcelain commands will do some extra stuff to update our branch to point it at our new commit. As things stand right now our branch isn’t pointing to anything at all.

/tmp/example [master] » git log

fatal: your current branch 'master' does not have any commits yet

I’ll come back to HEAD and branches later.

commit hierarchy

Commit objects usually point to their “parents” which are of course also commit objects, this effectively lets us walk backwards through commit objects viewing the state of the project as it looked at that moment in time. You can think of a commit object as a snapshot of the project file system.

Let’s add a new file to our project and generate a new commit object, except

this time we will specify the previous commit 86eb47 as the parent of the new

commit using the -p option.

/tmp/example [master] » vim README.md

/tmp/example [master] » git update-index --add README.md

/tmp/example [master] » git write-tree

862d1dff20b9783d304b6188999f8a01bdab2956

/tmp/example [master] » echo "Second commit" | git commit-tree 862d1d -p 86eb47

086a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

We now have a new commit object 086a49, if we print out the contents using

cat-file we will see all the information that we saw in our first commit

object, only this time there is a new line saying that tree 86eb47 is the parent

of this new commit object.

/tmp/example [master] » git cat-file -p 086a49

tree 862d1dff20b9783d304b6188999f8a01bdab2956

parent 86eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341

author Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev> 1595069781 +0100

committer Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev> 1595069781 +0100

Second commit

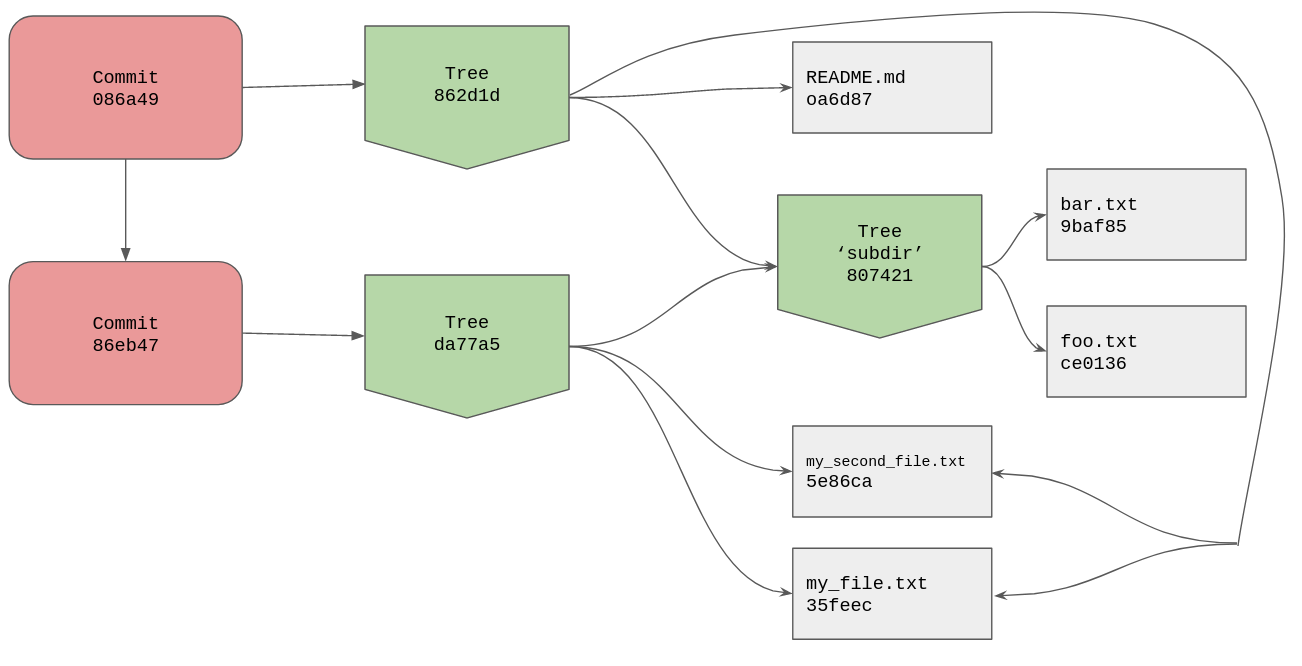

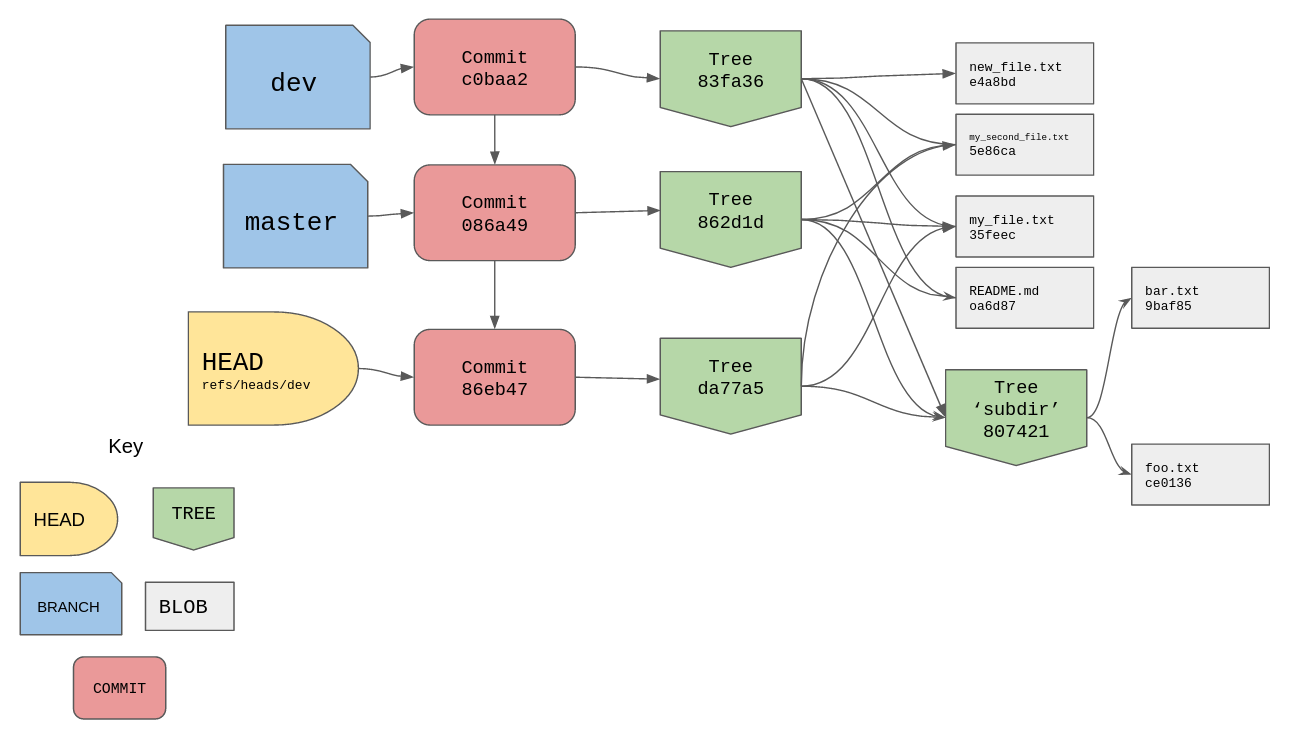

A diagram to show the relationships between the objects we currently have in our objects directory would be helpful here I reckon.

What we have done here with our commits is create a directed acyclic graph

(DAG), our commits only

go in one direction and there are no cycles. Our most recent commit 086a49

points to tree 862d1d, and its parent is commit 86eb47 which points to tree

da77a5. The trees for each commit show the project directory at different

stages, these are our snapshots.

With the diagram we can see that our most recent tree object references the same

blob objects for my_file.txt and my_second_file.txt, we haven’t changed them

since the initial commit.

Seeing as we now have a small chain of commits we can view them with git log <commit-hash>.

/tmp/example [master] » git --no-pager log 086a49

commit 086a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sat Jul 18 11:56:21 2020 +0100

Second commit

commit 86eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sat Jul 18 11:23:42 2020 +0100

Initial commit

We have to pass in the commit hash because if we run git log without a hash

git will use HEAD by default, and the branch that HEAD points to isn’t

pointing to any commits, git log would have nothing to show. Hence you get

this error back.

/tmp/example [master] » git log

fatal: your current branch 'master' does not have any commits yet

We’ve covered blobs, trees, and commits, the final kind of object that git can store is something called an annotated tag. Tagging isn’t relevant to this post but you can read more about tagging at git-scm.com.

I think it’s time we moved on from the .git/objects directory and we had a

chat about the .git/refs directory.

references

Looking at our object database right now we have a lot of objects but how to do we keep track of the commit object we are currently working off? The commit objects are in there somewhere but unless we remember the hash for them they quickly get lost amongst the other objects.

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/86/eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341

.git/objects/86/2d1dff20b9783d304b6188999f8a01bdab2956

.git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

.git/objects/ce/013625030ba8dba906f756967f9e9ca394464a

.git/objects/08/6a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

.git/objects/80/742180d72a4a91376be94367991f9b498e72f7

.git/objects/5e/86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214

.git/objects/7e/fe94e736bc17a55fda2b8b5bc6e125c1454ea4

.git/objects/da/77a56b7a85f94f957b97ba3bc10e089e3daea0

.git/objects/9b/af85eb7aa8e3dda46b3388b4ad32841cff85fa

.git/objects/35/feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2

.git/objects/0a/6d871132585640d7ca545325ba6232a7a2044d

The answer is branches. A branch in git is just a pointer to a commit object,

and by that I mean a branch is just a file that lives in the .git/refs/heads

directory, and its only content is a commit object hash. If we look inside the

refs directory right now we will find it’s completely empty. No branches

currently exist.

/tmp/example [master] » ls .git/refs/heads

/tmp/example [master] »

Hold on, aren’t we on the master branch right now? What do you mean it doesn’t exist?

Astute observation dear reader, nothing gets by you. Yes we are on the master

branch but it isn’t currently pointing to any commit, hence the lack of a file.

The reason we are technically on master right now is due to the .git/HEAD

file, it holds a reference to your current branch.

/tmp/example [master] » cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/master

Let’s update master to actually point to a commit, to do so we can use

the update-ref plumbing command.

/tmp/example [master] » git update-ref refs/heads/master 086a49

/tmp/example [master] » ls .git/refs/heads

master

I’ve told git to update the reference refs/heads/master to point to our latest

commit object, git then creates the reference by adding a file to our

.git/refs/heads/ directory called master and if we cat the file you’ll see

all that it contains is a commit hash.

/tmp/example [master] » cat .git/refs/heads/master

086a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

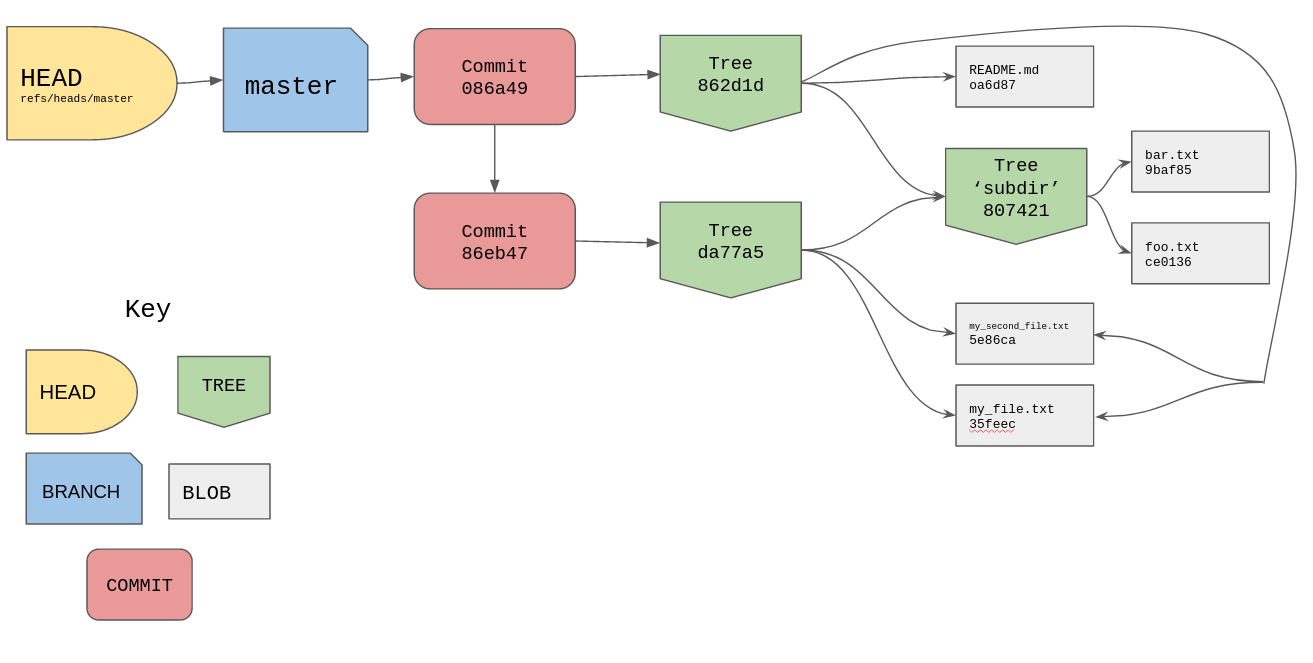

Let’s add this new master ref and the HEAD file to our diagram from earlier.

branching

Okay cool, this all makes sense so far (I hope). What happens then if we were to

branch off master to do some feature work? I’ll just use a normal porcelain

command that we are all familiar with.

/tmp/example [master] » git checkout -b dev

Switched to a new branch 'dev'

/tmp/example [dev] » ls -l .git/refs/heads

total 8

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 41 Jul 18 13:25 dev

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 41 Jul 18 13:10 master

A couple of things happened here. First git has created a new branch which we

find in the .git/refs/heads directory as a file called dev. If we look in

the file we should find the commit hash that master is also currently pointing

to.

/tmp/example [dev] » cat .git/refs/heads/dev

086a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

It also updated HEAD to point to this new branch.

/tmp/example [dev] » cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/dev

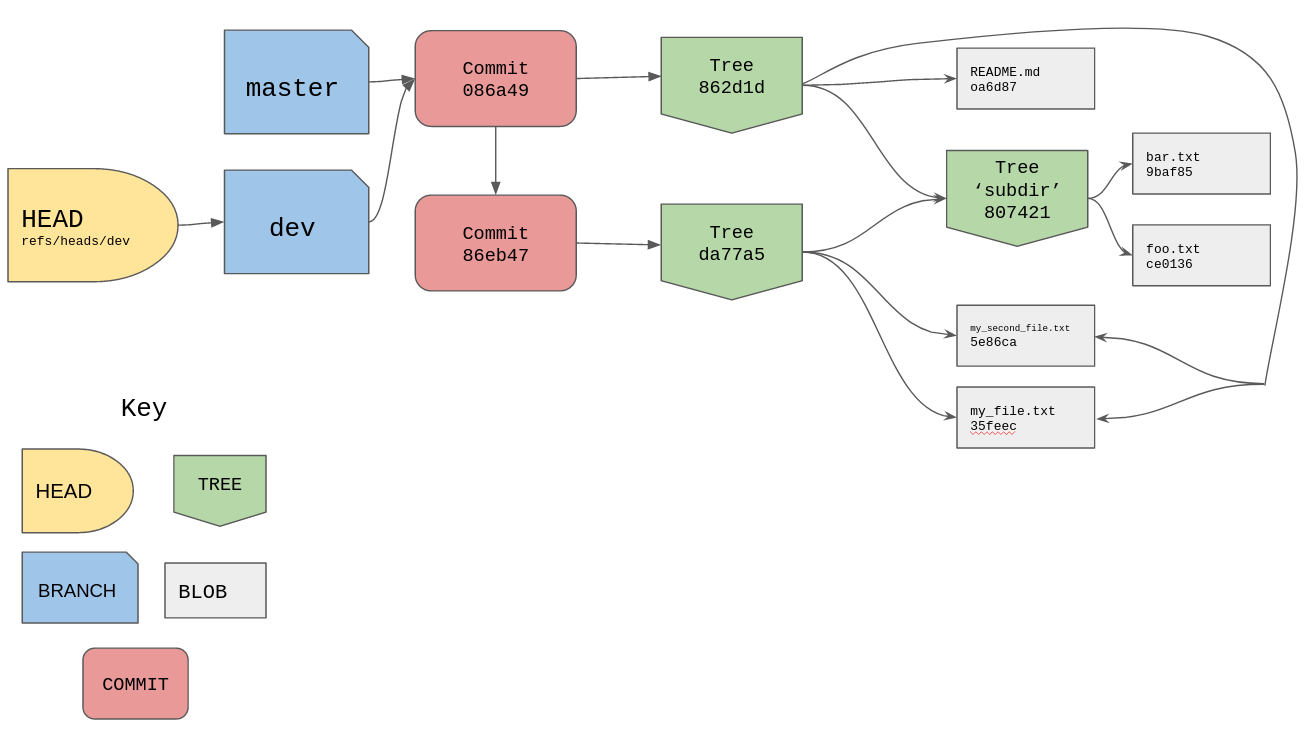

I’ll update the diagram from before to include this new branch.

Let’s then do some work on this new branch, let’s edit new_file.txt and seeing

as I have been through the process of adding files and creating new references

with plumbing commands I’ll use porcelain commands to quickly create a new commit.

/tmp/example [dev] » vim new_file.txt

/tmp/example [dev] » git add .

/tmp/example [dev] » git commit -m "important work"

[dev c0baa27] important work

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 new_file.txt

By now you should understand that the porcelain commands have hashed

new_file.txt, stored the resulting object in our objects directory, staged

the changes in our index, then they created a new tree object, created a new

commit object using that tree, and then pointed the dev branch at this new

commit. Seeing as HEAD points to our branch we can just use that to inspect

the latest commit object. HEAD -> refs/heads/dev -> commit hash.

/tmp/example [dev] » git cat-file -p HEAD

tree 83fa36cec1ec042e517cf95609830f4eaff8ce62

parent 086a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

author Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev> 1595075640 +0100

committer Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev> 1595075640 +0100

important work

If you would like to see what commit a branch points to you can use the

rev-parse plumbing command.

/tmp/example [dev] » git rev-parse HEAD

c0baa27f61e6691a54a1bfcd648dc81995d77c3d

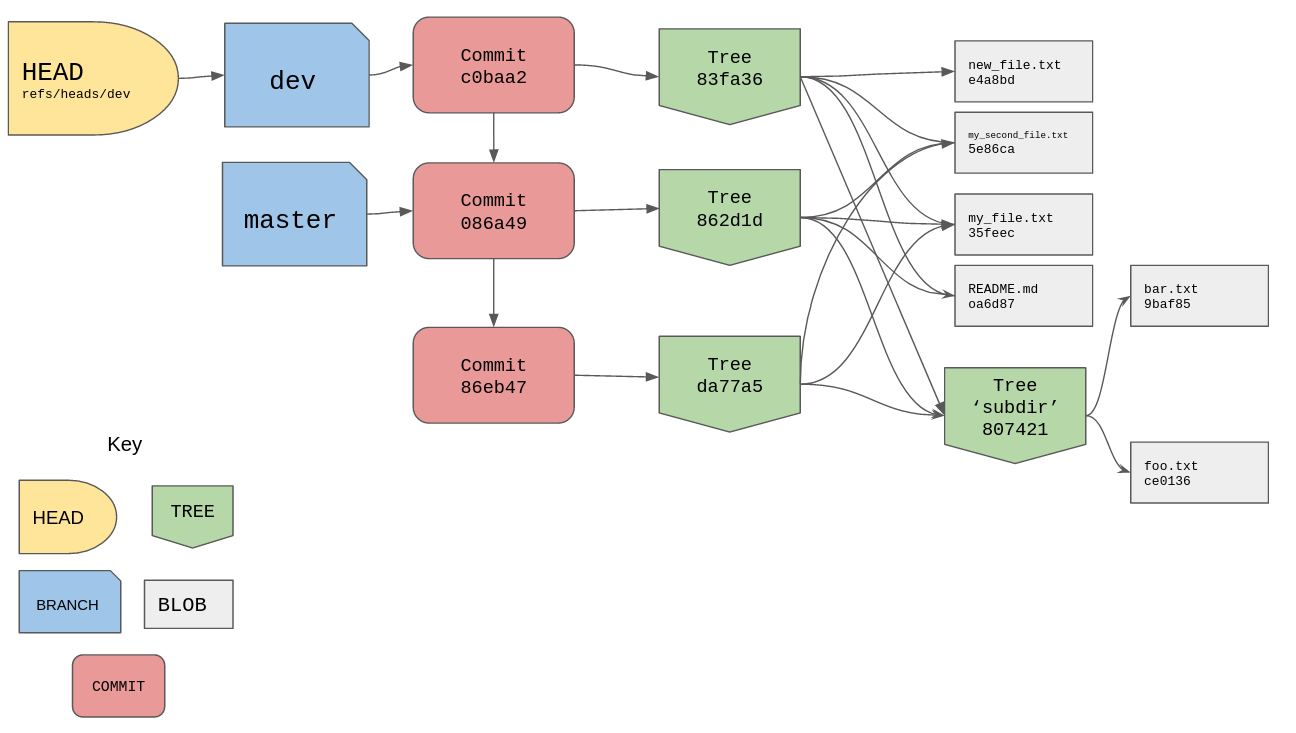

And here is the current state of our project, note the two versions of

new_file.txt. The new one is only referenced by the latest commit whilst the

old one is referenced by older commits.

The commit c0baa2 is the latest commit and the branch dev is pointing to it,

the parent of c0baa2 is the commit 086a49 which the branch master is still

pointing to. If we were to checkout master then merge in dev, git would see

the commit that dev is pointing to is reachable from the commit master is

pointing to, so it just performs a “fast-forward” merge by updating

refs/heads/master to point to c0baa2. I won’t mess with the branches though,

I’ll leave them as they are.

detached head

So far in our branching adventures we have created a new branch off master

called dev then checked that branch out, our HEAD file was updated along the

way. HEAD likes to point to branches, however we aren’t limited to just

branches, we can point HEAD at a commit object if we really wanted to. Let’s

use our initial commit 86eb47.

/tmp/example [dev] » git checkout 86eb473

Note: checking out '86eb473'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b <new-branch-name>

HEAD is now at 86eb473 Initial commit

Oh no, a detached head warning! Not to worry, this okay, we haven’t broken

anything. Git likes HEAD to point to a known branch, the reason being if we

were to do some work and create a new commit, that new commit won’t be

referenced by any branch. So if you then move HEAD by checking out another

branch, you run the risk of losing that commit unless you remember the hash. In

short you could “lose” work, even though it exists in the objects directory you

might not find it again.

Here is our diagram now showing HEAD pointing to the initial commit whilst the

master and dev branches stay pointing to their own commit objects.

git reflog

I would like to quickly add here that it’s quite hard to lose work with git.

Git will keep a record of every branch and commit object (AKA refs) that HEAD

has pointed to. If you had ended up in a detached head state, edited some files,

created a new commit, then navigated away from it you could run git reflog to

find out what the commit hash was, then run git checkout <commit-hash> to get

it back.

/tmp/example [master] » git --no-pager reflog

086a493 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{0}: checkout: moving from 86eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341 to master

86eb473 HEAD@{1}: checkout: moving from fc3f772c07dd87e8100bce03f2ccc520d09887c0 to HEAD^

86eb473 HEAD@{3}: checkout: moving from dev to 86eb473

c0baa27 (dev) HEAD@{4}: commit: important work

086a493 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{5}: checkout: moving from master to dev

086a493 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{6}:

reflog has saved my ass more times than I can count, keep it in your back

pocket.

pack files

We are nearing the end of our journey through the internals of git and I want to

end on how git saves space. If we look at our objects directory we have a fair

amount of objects in there, these are technically called “loose objects”. The

reason will become apparent soon enough.

/tmp/example [master] » find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/86/eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341

.git/objects/86/2d1dff20b9783d304b6188999f8a01bdab2956

.git/objects/c7/c7da3c64e86c3270f2639a1379e67e14891b6a

.git/objects/ce/013625030ba8dba906f756967f9e9ca394464a

.git/objects/83/fa36cec1ec042e517cf95609830f4eaff8ce62

.git/objects/08/6a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94

.git/objects/8b/137891791fe96927ad78e64b0aad7bded08bdc

.git/objects/80/742180d72a4a91376be94367991f9b498e72f7

.git/objects/5e/86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214

.git/objects/c0/baa27f61e6691a54a1bfcd648dc81995d77c3d

.git/objects/7e/fe94e736bc17a55fda2b8b5bc6e125c1454ea4

.git/objects/da/77a56b7a85f94f957b97ba3bc10e089e3daea0

.git/objects/9b/af85eb7aa8e3dda46b3388b4ad32841cff85fa

.git/objects/e4/a8bd934d846883e883c85b7e3cbfc62e4e7f64

.git/objects/35/feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2

.git/objects/0a/6d871132585640d7ca545325ba6232a7a2044d

.git/objects/79/0bfa0735f612b82a2575226b8c7768e6aa0daa

We can use another plumbing command count-objects to count our objects for us,

the -H command just makes the total size human-readable.

/tmp/example [master] » git count-objects -H

17 objects, 68.00 KiB

We can tell git to run an algorithm to work out similar files, generate the

deltas (diffs) between them, and just store those instead in something called a

pack file. The command to do this gc which stands for garbage collect, git

will do this automatically and regularly over the course of a project’s life

time so it’s rare to need to run this yourself.

/tmp/example [master] » git gc

Enumerating objects: 13, done.

Counting objects: 100% (13/13), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (7/7), done.

Writing objects: 100% (13/13), done.

Total 13 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

/tmp/example [master] » git count-objects -H

4 objects, 16.00 KiB

Git has cleaned up our objects for us leaving us with only 4 objects and it

reduced the size of our objects by a decent amount. If we look in the

.git/objects directory we can finally look at the pack directory that I

slyly ignored earlier.

/tmp/example [master] » ls -l .git/objects

total 24

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 14:20 79

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 11:04 7e

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 14:20 8b

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 10:10 c7

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 14:31 info

drwxr-x--- 2 skip skip 4096 Jul 18 14:31 pack

/tmp/example [master] » ls -l .git/objects/pack

total 8

-r--r----- 1 skip skip 1436 Jul 18 14:31 pack-4f70170bbdd3b31bfb07548b93d2ae065e967572.idx

-r--r----- 1 skip skip 956 Jul 18 14:31 pack-4f70170bbdd3b31bfb07548b93d2ae065e967572.pack

The .pack file is a binary file where all our objects and deltas are stored

and the .idx file is the index file to help git find what it needs in the pack

file. We can look inside the pack file using the verify-pack plumbing command,

passing the -v flag makes the command verbose so we actually see some output.

/tmp/example [master] » git verify-pack -v .git/objects/pack/pack-4f70170bbdd3b31bfb07548b93d2ae065e967572.pack

c0baa27f61e6691a54a1bfcd648dc81995d77c3d commit 241 162 12

086a49350403eb04f3bdddc6e122f5125305da94 commit 240 159 174

86eb4733b913aadb7929c8b3c9f5dae7340e2341 commit 193 130 333

35feeca61f9714951452c46d7ab5cef59e3939f2 blob 25 35 463

5e86ca0a991775dcf29e69570198b4c7de889214 blob 20 30 498

9baf85eb7aa8e3dda46b3388b4ad32841cff85fa blob 8 15 528

ce013625030ba8dba906f756967f9e9ca394464a blob 6 15 543

83fa36cec1ec042e517cf95609830f4eaff8ce62 tree 195 175 558

862d1dff20b9783d304b6188999f8a01bdab2956 tree 40 51 733 1 83fa36cec1ec042e517cf95609830f4eaff8ce62

da77a56b7a85f94f957b97ba3bc10e089e3daea0 tree 6 16 784 2 862d1dff20b9783d304b6188999f8a01bdab2956

80742180d72a4a91376be94367991f9b498e72f7 tree 70 75 800

0a6d871132585640d7ca545325ba6232a7a2044d blob 17 27 875

e4a8bd934d846883e883c85b7e3cbfc62e4e7f64 blob 24 34 902

non delta: 11 objects

chain length = 1: 1 object

chain length = 2: 1 object

.git/objects/pack/pack-4f70170bbdd3b31bfb07548b93d2ae065e967572.pack: ok

All of our objects are in here, our blobs, our trees, and our commits. Safe and sound.

round up

That was a LOT of information and if you made it this far I hope you learned some stuff along the way, let me just sum up the main points:

- the

.gitfolder is the entire repo. - git is a content addressable filesystem.

- a blob object represents file contents.

- a tree object represents a directory.

- a commit object is a snapshot of your project, it points to a tree.

- branches are just pointers to commit objects.

- the

HEADis just a pointer to a reference/branch. - “detached head state” just means

HEADis pointing to a commit object.

If you understand all of the above then congratulations you understand git internals! Even knowing half of the information in this post will help you understand what git is doing when it ends up in a weird state.

If you want to read more about git’s internals I advise reading git-scm.com, their free book has been my main reference throughout this post.

Remember, git is just a tool so don’t let it get the better of you. Read about it, understand it, and you’ll thank me later.