git revert

03 Oct 2020 | categories: blog

prev: Ruby Modules | next: git reset

So you’ve fucked up. You’ve merged something and production did an oopsie but you’ve managed to stop the bleeding by turning off the feature flag that guards your new feature (you did feature flag it, right?), now you need to revert your changes. I’m not sure why you’re reading blog posts when you should be working but I guess it’s a good thing you’re reading this one.

Reverting is quite a simple thing but there are aspects of it that have tripped me up in the past, I’ve even seen some seasoned engineers get tripped up too. I would like to go through the steps of reverting a commit with git and explain what happens so you can feel confident making these changes yourself.

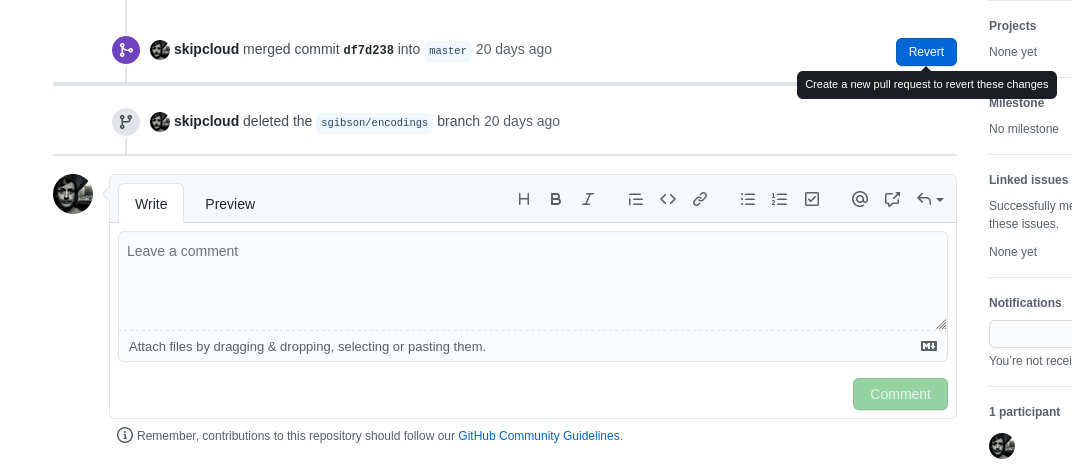

github

If you’re using github then you can easily open a pull request to revert a merged pull request just by clicking a button.

This one isn’t rocket science and it’s usually the one you reach for when you

need to revert something from the master branch. However there are times when

you need to use the command line to revert something, for example some services

in Deliveroo have a workflow that uses a staging branch which you manually

merge development branches into and push to the remote, these new changes kick

off a continuous integration

(CI) pipeline and

eventually get deployed to a staging area for testing.

If I were to merge a bad change to staging and break the CI pipeline then I

would have to manually revert my merge and push it in order to unblock my

colleagues. Knowing how to revert code can come in handy so let’s go hangout on

the command line and see how to revert some commits.

command line reverts

Reverting a commit in git is as easy as git revert <commit>.... However

depending on what you’re trying to achieve you will need to use revert in

different ways, hell sometimes revert isn’t even the right command to use.

Let’s set the stage so we have some examples to work through, I’ve got two

branches master and dev.

A--B master

\

C--D dev

master has two commits A and B, dev branched from master on commit B

and then made two more commits C and D.

If we were to merge dev into master right now then git would just perform a

fast-forward merge because it can see that master is pointing at commit B

and B is an ancestor of commit D.

Therefore git checkout master && git merge dev would result in this:

A--B--C--D master

^

└─ dev

Nice and clean, git takes the commits C and D and replays them in order on

commit B and we end up with a lovely line of commits and the history is simple

to follow.

We can use git log to graph out the new history but it won’t be very

interesting because as I’ve just shown you the history is a straight line.

∵ git --no-pager log --graph --oneline

* 0bac119 (HEAD -> master, dev) D

* d2f6871 C

* 72e6e90 B

* a9b6059 A

Now, we would like to undo this fast-forward merge and to achieve that goal we have

two options, it depends on whether we want to keep the history of what has

happened whilst undoing the changes OR we can just blow away the changes all

together and restore master to its previous state before the merge occurred.

Let’s start with the latter.

reset

This action is simple, we know we want master to point to commit B again and

we know the hash for the commit is 72e6e90. We simply just use git reset to

point the master branch at this commit.

∵ git reset --hard 72e6e90

HEAD is now at 72e6e90 B

The --hard option here tells git to throw away any changes and leave the

working directory clean. Everything should look just like it did at the start of

this exercise. dev has not been affected by this command and the commits C

and D still exist, they just aren’t part of the master branch any longer.

A--B master

\

C--D dev

If master was pushed to the remote before we did the reset then we would need

to force push these changes and rewrite history so the remote branch mirrors our

local one, but perhaps master is protected and the remote will reject the

force push or maybe you’re working with others on this project and don’t want to

ruin their day by rewriting history.

In that case we can’t use the reset option and we need to revert.

reverting a fast-forward

Okay, pretend the git reset never happened and we have merged dev into

master and our commit history looks like this again.

A--B--C--D master

We know we want to undo C and D so we could either issue two commands

reverting those commits:

∵ git --no-pager log --oneline

0bac119 (HEAD -> master, dev) D

d2f6871 C

72e6e90 B

a9b6059 A

∵ git revert 0bac119

[master 1bd732b] Revert "D"

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 file4

∵ git revert d2f6871

[master 059f217] Revert "C"

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 file3

∵ git --no-pager log --oneline

059f217 (HEAD -> master) Revert "C"

1bd732b Revert "D"

0bac119 (dev) D

d2f6871 C

72e6e90 B

a9b6059 A

We work backwards through the commits reverting each as we go and this results

in two new commits being added Revert "D" and Revert "C". Instead of doing

each separately we could have passed both hashes to the command, i.e. git revert

0bac119 d2f6871 which would achieve the same thing.

If you need to revert a load of commits then it makes more sense to use a gitrevision to specify a range of commits that we want to revert and git will take care of figuring out which commits to revert and in what order. Gitrevisions are really powerful things and I’m going to write a post specifically about them at some point, for now though let’s get on with reverting.

I’ll undo the previous revert and specify a range of commits instead.

∵ git revert 72e6e90..HEAD

[master 19b7a23] Revert "D"

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 file4

[master 099890b] Revert "C"

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 file3

∵ git --no-pager log --oneline

099890b (HEAD -> master) Revert "C"

19b7a23 Revert "D"

0bac119 (dev) D

d2f6871 C

72e6e90 B

a9b6059 A

This means our commit history now looks like this with dev still pointed at

commit D:

A--B--C--D--!D--!C master

^

└─ dev

I’m using an exclamation point to show the commit is a revert. It’s important to keep in mind that reverting doesn’t remove commits, it just adds new ones that undo the changes.

What do you think happens if we try to merge dev back into master? For a lot

of people they think all of the changes from dev will be reapplied, but right

now nothing will happen. This surprised me initially and it confused me for the

longest time.

∵ git merge dev

Already up to date.

Remember that dev is pointing at commit D and when you merge branches in

git it will look back in time for when dev branched from master, it does

this by looking for a common ancestor (AKA the base commit) and uses that to

work out how to merge the two branches.

In this instance git will see that the commit D that dev points to is

already part of master’s history so there’s nothing to add.

But what if we had made some changes on dev, perhaps some commits that fixed

problems in C and D? Our history now looks like this:

A--B--C--D--!D--!C master

\

E--F dev

What makes this slightly insidious is if we tried to merge with master then

only the new commits E and F would be merged and if these commits relied on

code in the older reverted commits C and D then you’re in for a surprise

when the code doesn’t work because the code was undone by !C and !D.

What we would need to do is rebase dev onto !C then revert the revert

commits !C and !D in exactly the same way we reverted C and D in the

first place to re-introduce the code before merging in dev, something like

this:

A--B--C--D--!D--!C---------------G master

\ /

!!C--!!D--E--F dev

It’s messy but if you cannot reset master then it might be your only option.

So that’s how you go about reverting a fast-forward merge, what do you do when

you’re dealing with a true merge commit like commit G?

reverting a merge commit

Jump back in time a little to when our branches looked like this, before we started fucking around with reverting reverts.

A--B--C--D--!D--!C master

\

E--F dev

If we merge dev into master now we would no longer get a fast-forward

merge because master contains commits that aren’t part of dev’s history. We

would instead get a true merge which results in a merge commit.

What happens is git sees there are commits on master that aren’t part of

dev’s history so it replays dev’s commits on the latest commit on master

one after the other. Provided there are no merging conflicts then everything

should merge cleanly resulting in a new merge commit:

∵ git merge dev

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

file5 | 0

file6 | 0

2 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 file5

create mode 100644 file6

∵ git --no-pager log --graph --oneline

* a1398c6 (HEAD -> master) G

|\

| * acacc56 (dev) F

| * ea4cafc E

* | 099890b Revert "C"

* | 19b7a23 Revert "D"

|/

* 0bac119 D

* d2f6871 C

* 72e6e90 B

* a9b6059 A

Now for whatever reason we need to revert this merge commit so we try running

git revert HEAD, remember HEAD for master is pointing at commit G but you

could also supply the hash a1398c6 if you’re feeling saucy.

∵ git revert HEAD

error: commit a1398c6825c2e1dddf781e0f8f49423ae144e56a is a merge but no -m option was given.

fatal: revert failed

Huh. An error. Apparently we need to give it the option -m?

When I first encountered this problem I was told:

Oh that happens sometimes, just pass the option “-m 1” and it’ll work.

I did what I was told and sure enough that fixes the problem:

∵ git revert -m 1 HEAD

[master 3f336fb] Revert "G"

2 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 file5

delete mode 100644 file6

Okay but why does it fix the problem? What was the problem in the first place?

If we use git log to look at the merge commit G we will see some extra

information in there that isn’t present in a normal commit.

∵ git --no-pager show -1

commit a1398c6825c2e1dddf781e0f8f49423ae144e56a (HEAD -> master)

Merge: 099890b acacc56

Author: Skip Gibson <skip@skipgibson.dev>

Date: Sat Oct 3 13:14:20 2020 +0100

G

I’m specifically talking about the line Merge: 099890b acacc56, what this

says is “here are the heads of two branches that were merged to make this

commit”.

When you try to revert a merge commit git has no way of knowing what set of

changes you want to undo. Do you want to revert the line of history for

099890b or acacc56? In other words what side of the merge should be

considered the mainline, in fact -m stands for --mainline.

If we jump back in time a little just before we reverted the merge our commit history looks like this:

A--B--C--D--!D--!C--G master

\ /

\----E--F dev

Because we merged dev into master then master is considered our 1st

line and dev is considered our 2nd. When we pass -m 1 to git revert git

knows to keep all the changes on the master branch which leaves us with this

history:

A--B--C--D--!D--!C master

\

E--F dev

If we were instead to pass -m 2 then git would revert everything in the

master line to the point where dev and master branched from each other, in

other words up to commit D undoing !D and !C.

We would effectively get this history:

A--B--C--D--E--F master

^

└─ dev

Now it isn’t actually this clean in reality as the revert results in a new

revert commit but in essence all of the changes from A through F would be

visible on master.

Here is what it looks like in real life:

∵ git revert HEAD -m 2

[master ad7255b] Revert "G"

2 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 file3

create mode 100644 file4

∵ git --no-pager log --graph --oneline

* ad7255b (HEAD -> master) Revert "G"

* a1398c6 G

|\

| * acacc56 (dev) F

| * ea4cafc E

* | 099890b Revert "C"

* | 19b7a23 Revert "D"

|/

* 0bac119 D

* d2f6871 C

* 72e6e90 B

* a9b6059 A

Selecting the dev branch as the mainline in our revert means when you trace

the commit history backwards from G you would take the path on the right

leading to F to E which joins back up with commit D etc.

As I was working through these examples I’ve added a new file with each commit,

commit A added file1, commit B added file2 etc, so if I list the

contents of the directory right now we should see 6 files corresponding to each

commit A to F:

∵ ls -l

total 0

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 0 Oct 3 09:19 file1

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 0 Oct 3 09:19 file2

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 0 Oct 3 13:34 file3

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 0 Oct 3 13:34 file4

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 0 Oct 3 13:24 file5

-rw-r----- 1 skip skip 0 Oct 3 13:24 file6

conclusion

Git seems scary and it looks like it does crazy shit at times but in reality it is very logical and once you’ve got a good mental model of what it is doing it’s much easier to reason about the seemingly crazy stuff it does.

Remember:

-

Reverting just adds a new commit undoing the changes of the commit you’re reverting.

-

Reverting a merge commit means you need to tell git which line of history to keep using the option

--mainline. -

If you don’t need to keep the history then just use

git reset --hardto undo your changes.